OCD is a relatively common developmental disease that affects all types of horses.

In order to understand how OCD occurs, we must first understand how joints develop in the womb and the first few months of life.

Development of bones and joints occur through a process known as endochondral ossification. This is responsible for the formation of normal bone as well as the smooth covering on the ends of bones (articular cartilage).

Normal pain-free joint function depends on this smooth cartilage surface with a strong supporting plate of bone underneath.

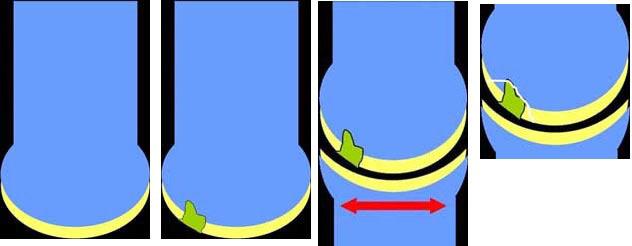

Failure of the developmental process leads to a disturbance in the formation of cartilage and the underlying bone (Figures 1a-d).

The resultant cartilage and bone is irregular in thickness and weaker than normal. Forces placed on these areas lead to several problems which are recognized as OCD; these include detachment and fracture of cartilage and variable sized pieces of bone.

These detached and fractured areas usually remain partially attached to the surrounding tissue or occasionally become completely detached and free-floating within the joint. Either way they cause irritation and inflammation within the joint and resultant lameness

Figure 1. Normal development results in a bone (shown in blue) with a subchondral bone plate to which a smooth cartilage cap is attached (shown in yellow).

Figure 2. Abnormal development due to a defect in endochondral ossification results in an area of thickened and/or weakened abnormal bone and cartilage (shown in green).

Figure 3. Trauma or exercise can further damage the abnormal area as the horse flexes and extends the joint.

Figure 4. Separation of the abnormal bone and cartilage from the underlying and surrounding tissue results in an OCD fragment, which can form a flap or can detach and float as a free body within the joint.

Several causes of OCD are known, although the disease is generally considered to be multifactorial. As a result, the disease is not usually caused by any one factor, but rather a combination of several factors acting together. These known factors include:

Rapid growth and large body size: An unusually rapid phase of growth and/or growth to a large size can be associated with OCD formation. OCD in ponies is relatively rare

Nutrition: Diets that are high in energy or have an imbalance in trace minerals can lead to OCD formation.

Genetics: Risk of OCD may also be partially inherited, although the mode of inheritance is not well defined and other factors are often required before an OCD fragment forms.

Hormonal imbalances: Imbalance in certain hormones during development, including insulin and thyroid hormones, can encourage OCD formation.

Trauma and exercise: Trauma to a joint, including routine exercise, is often involved in formation and loosening of the OCD flap or fragment.

Since all these factors are often involved it is currently not possible to predict which horses will develop OCD, and is therefore difficult to prevent the formation of OCD in individual animals. Clinical prevalence of OCD is usually between 5-25% in any given horse population.

Signs and symptoms

OCD may be detected as early as five months of age or as late as skeletal maturity (approx three years of age).

The most common sign of OCD is effusion (swelling) within the joint (Fig 2).

Depending on the location and severity of OCD, the horse may be noticeably lame on the limb, may only be lame during high-speed work, or may have minimal detectable lameness at all. OCD can occur in virtually all joints, however the most commonly affected are the hock, the stifle, and the fetlock.

Any young horse with a swollen joint (see far left) should be examined by a vet in order to properly diagnose OCD and to rule out other causes of joint distension.

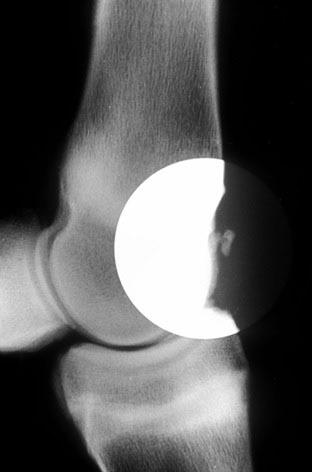

Diagnosis of OCD involves careful joint examination, a lameness examination, and radiographs. Since OCD is often bilateral, radiographs of the opposite joint is usually indicated.

OCD fragments will usually show up on the radiograph as a piece of bone that seems detached from the parent bone (Figs 3 and 4).

Occasionally an OCD fragment is made entirely of cartilage and cannot be seen on the radiograph; only the defect in the main bone may be visible on X-ray in these cases.

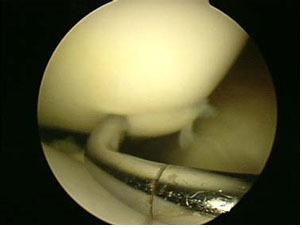

In most cases, OCD is best treated by surgical removal of the abnormal bone and cartilage. The most common technique used for surgical removal of OCD fragments is keyhole surgery (Figure 5).

Arthroscopic OCD fragment removal usually requires general anaesthesia. The surgeon makes two or more small incisions into the joint through which an arthroscope is placed to visualise the joint and instruments are introduced in the other incision to remove the fragment(s).

Figure 5. This is an arthroscopic view of an OCD fragment in a stifle joint. A blunt probe is being used to palpate the fragment. Notice how the fragment is slightly raised above the surrounding cartilage and there is a clear line of separation between the fragment and the surrounding tissue.

Following proper treatment, the prognosis for athletic function is good to excellent for many types of OCD.

Some OCD locations, such as the shoulder, may have a reduced prognosis.

It is important to discuss the expected outcome, including appearance of the operated joint, with your veterinary surgeon.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article