WITH ever increasing costs of production, low ex-farm prices, financial support very much on the wane and unpredictable weather, farming in Scotland is far from easy and the further north your travel, the more difficult it definitely becomes.

Mainland Scotland is challenging enough, but add another 175 miles from the north tip of Scotland, Wick, to Lerwick on Shetland, and not only do you have to face some seriously long, dark winter days and indeed nights, but also significantly higher input costs.

In fact, the sheer cost of freight to and from the island, means a single large round bale of straw will cost about £40, with concentrate feeding costing a further £40 per tonne more on Shetland than on mainland Scotland.

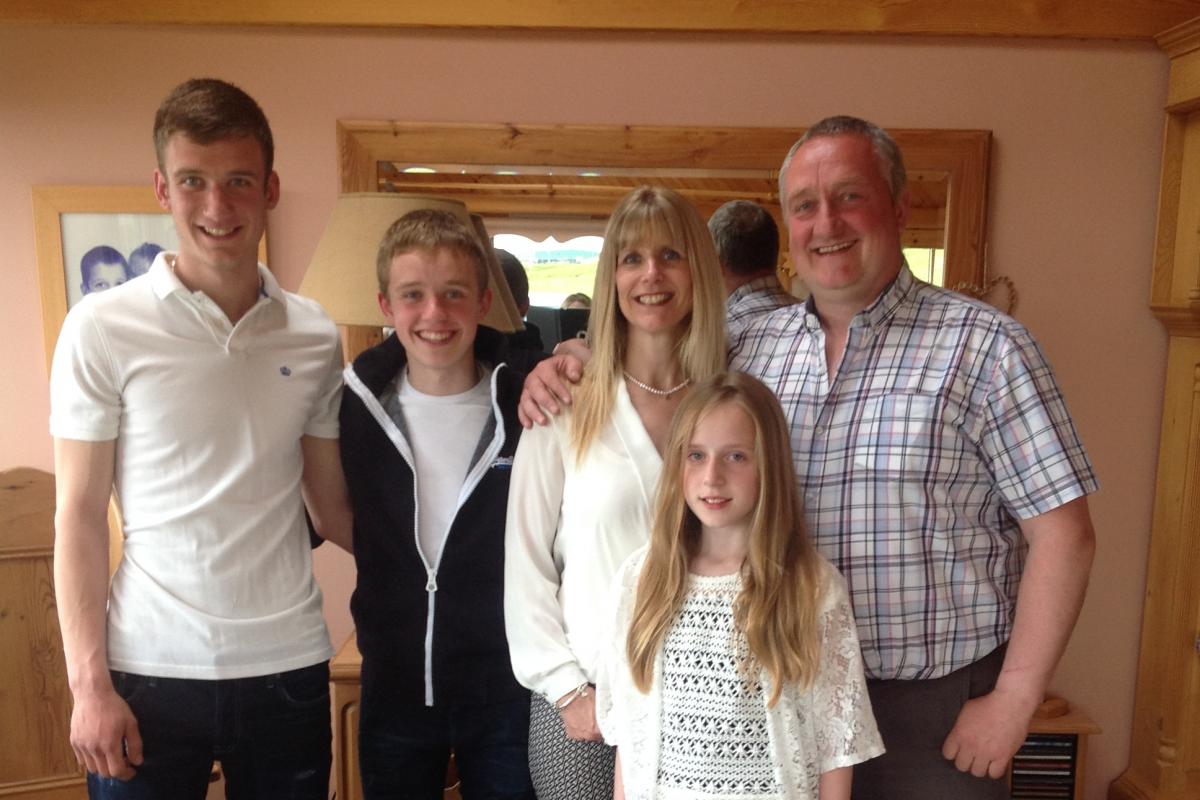

Yet, despite the difficulties, Eric Graham, his wife Jacqui and family of Sean (19), Liam (16) and Vhairi (13), wouldn’t farm anywhere else.

They have had plenty of opportunities too, as Eric has previously worked in the oil industry, the retail sector and on farms in central Scotland.

Deprived of any real warm summer sunshine and at the mercy of some extremely wet weather and long winters, the Grahams remain happiest farming their 1900-acre hill unit at Gremista, Lerwick.

Instead, Eric insisted Shetland is a great place to live – in spite of the weather and the winter darkness.

“There is a real sense of community spirit here and a sense of belonging. With sound investment having been made in the past due to the revenue from the oil industry we have brilliant leisure facilities and an excellent infrastructure, therefore there is always something to do for young and old, without forgetting our many Up- Helly-Aa celebrations which lighten up our darker months of the year!

“There are alcohol and drug issues within the isles but at a very different level, compared to many areas on the mainland. There is no major crime to speak of either and because the people are so friendly, we find visitors keep coming back to Shetland,” added Eric, whose wife, Jacqui, works in a Children’s Halls of Residence while their eldest son, Sean works at home. Liam is an apprentice mechanical engineer with Honda on the island. Liam and their daughter Vhairi (13) are also keen to help on the farm.

There is always plenty to do, as with 940 ewes and 25 cows to attend to and all their offspring, there is never a dull moment.

With most of the farm comprising of heather hill which rises to 500ft above sea level, the family predominantly depends on native breeds, with the Shetland ewe very much at the forefront.

“Shetland sheep have a flavour all to themselves which makes the meat very succulent and sweet. It’s virtually organic here too so we can sell a lot of 10kg lambs to friends and neighbours,” added Eric. He also pointed out that many people who have had a bad experience of lamb-mutton come back for more once they’ve tasted Shetland lamb.

“The Shetland is also an extremely functional ewe that can be tupped to virtually any breed and produce a good lamb. She also works well in the conditions up here whereas Cheviots and Blackies, just don’t don’t perform as well in the environment.

“Shetland wool commands a premium too as the very best, superfine wool will sell for £2.50 per kg – we usually achieve a flock average of over £2.20 per ewe.

“They don’t cost a lot to keep either and there is always a good demand for breeding ewes as they do well with farmers on better ground on the mainland.

"Most wedder lambs are fattened and sold and shipped south for slaughter with ewe lambs retained for replacements with a few sold privately,” said Eric, who admitted the biggest problem with the breed is having good enough dogs to gather them!

In saying that, these small white sheep make up the bulk of the flock, with 500 bred pure on the hill producing lambing percentages of 90-95% sold.

They might not produce the largest lamb crops or the biggest lambs, but with little if any input costs – none of the hill ewes are scanned or fed and as they are grazed one ewe per ha and they are gathered only five times a year – they more than pay their way.

This hardy hill breed is also left to lamb itself, which in turn sorts out maternal issues regarding yeld ewes which are removed and taken home to be put to crossing rams and monitored at lambing time.

This has improved lambing percentages significantly among the hill sheep. The only input prior to lambing is gathering the ewes in to pull away some of the wool from each side of the udder, making it easier for lambs to gain access to that vital colostrum.

Further down the hill, 140 Shetland ewes are tupped to a Lleyn or a Cheviot to breed replacement females for the 250 Lleyn and Cheviot cross Shetland commercial ewes bred to a New Zealand Suffolk ram.

These females often produce lambing percentages of 150-160% at scanning and are lambed inside to safeguard the lambs from ravens, which are a serious problem on the island.

Similarly, the commercial ewe flock which produce lamb crops of 170-180% are also lambed inside alongside the flock of 50 pure bred North Country Cheviot ewes to breed home-bred tups and shearling rams to sell in the local market.

After cross ewe lambs have been drawn off as replacements, the top ewe lambs are sold for breeding at the local mart with prices ranging from £55-£65. The remainder are sold privately to regular customers.

Most years, 400 Suffolk and Cheviot cross lambs are sold finished off grass and pellets at 40-plus kg through local wholesalers too.

The best of the pure Shetland lambs, males and females are retained as replacements with others sold for breeding.

Well sought after in the market place, with Gremista-bred Shetlands, regularly winning awards at local shows, they have sold white Shetland rams to £2000 on three occasions with their pen of 20 averaging £350-£400 per head, while the annual consignment of 15-20 North Country Cheviot shearling rams have peaked at £800 to average £400.

Adding to an already busy work schedule are 25 Beef Shorthorn and Salers suckler cows, which are mostly bred pure with the best bull calves being retained for selling as rising two year olds.

Excess heifers are sold privately, with remaining progeny sold finished through the local abattoir. However, with the weather so wet, they are often inside from October to the end of June.

With the winters getting milder and wetter, not only are the cattle having to come inside earlier, leatherjackets and greylag geese are also becoming an increasing problem.

But on the plus side, there are no moles or foxes on the island. Instead, the biggest predator is the raven, with adolescents hunting in packs of up to 50 to prey on new-born lambs and couped ewes.

These big black 'vultures' are the source of much heartbreak on the island, but on the other side of the coin, they do eat some of the leatherjackets in the spring!

Ravens and geese cause serious problems on the island, but it is the Common Agricultural Policy and the UK government which is posing the biggest threat to farming and the entire way of life on the island.

“Farming is governed by paperwork and legislation now which is seriously impacting the industry and the people who work in it,” said Eric.

“Everyone is terrified to make a mistake as their basic payments can be severely penalised as a result and yet other industries get away scot-free. It would be fine if the money was there to pay for these mistakes, but lamb prices have been the same for the past 30 years.

“Farming is full of pressure now, which is why we see so much depression in the industry. We also have to face the fall in the level of financial support too, which we and many other farmers simply cannot survive without in the more peripheral and challenging parts of Scotland. Apart from anything else, how can we attract young people to live and work in the countryside, if the financial rewards cannot match their efforts concluded Eric.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article