A THIRD of the wheat grown in the UK still doesn’t receive sulphur applications – even though every cereal crop should have some sulphur applied to it, according to Tim Kerr, fertiliser manager with advice specialist, Hutchinsons.

Not all sulphur fertilisers are the same and timing will depend on a number of factors – but it is always useful to check what you are applying using the ‘4Rs’ system, he added.

“Ask yourself is it the right type of fertiliser; are you applying the right rate; are you applying it at the right time; and, finally, is it going on the right place?” said Mr Kerr.

Nitrogen and sulphur work closely together and demand for N and S is closely correlated, he added. One major function of nitrogen and sulphur is amino acid production and both elements are required together to ensure they are both utilised efficiently in this process.

“Currently, the most common current practice is for sulphur to be applied with nitrogen applications – generally with the first or second application. In fertiliser terms, there is a fixed ratio of the requirement of N and S – work on 5:1 for cereals.

“Between GS 31 and 39, N uptake averages 2.5kg/ha per day. At the same time, the S uptake is on average 0.5kg/ha per day. Between GS 39 and 59 N uptake averages 2kg/ha/ day and S uptake mirrors this at 0.4kg/ha per day.”

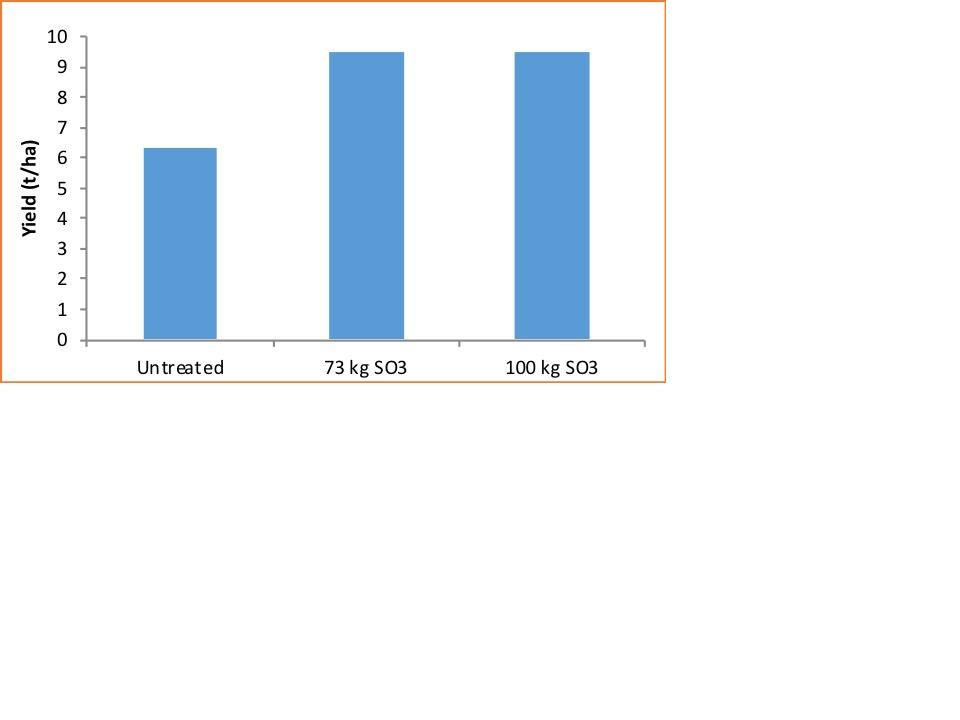

He referred to replicated trial work carried out by Yara and Hutchinsons in 2018 which showed a significant response to sulphur, though applying too much sulphur was of no economic benefit.

He said milling wheat growers should apply 50kg/ha of SO3 to reduce the risk of acrylamide formation during processing. “This is a good level to aim for – either that or use the 5:1 calculation, or 200 kg/ha of N = 40 kg/ha SO3.”

What product to use is also debateable. “There is frequent debate over the right choice of nitrogen fertiliser, whilst the suitability of the sulphur is often overlooked. Whilst ammonium sulphate is widely used and is rapidly available, it can also be at risk of significant nitrogen and sulphur losses.

“Whilst the risk of N losses via volatilisation from urea are well documented, research tells us that ammonium sulphate can be equally at risk of volatilisation on high pH soils – with potential nitrogen losses of the same magnitude as urea.

“Equally the sulphate fraction is water soluble – so can be prone to leaching below the rooting zone before it is utilised,” he pointed out.

Calcium sulphate is also used in some NS compounds and these would be more appropriate for alkaline soils and are less susceptible to leaching of sulphur. “It is, therefore, important to know what form of sulphur you are applying,” he added.

One alternative approach is to combine spring potash applications with sulphur. A new product now available to UK growers is Potash Plus (analysis 37% K2O, 3% MgO 23% SO3) which is a granular compound now being produced by ICL at the Cleveland Potash mine – it is a combination of MOP and polysulphate.

“The sulphur in polysulphate comes from three sources – calcium, magnesium and potassium sulphate. This has been shown to release S over a long enough period of time to meet the crop’s requirements for sulphur over the major growth period and is also unaffected by pH, so a useful alternative to ammonium sulphate.

“Applying potash in the spring is increasingly seen as an effective way of applying K to cereals to meet peak uptake requirements. The balance of K and S in Potash Plus will suit many UK soils and it could be a valuable addition to the toolbox for managing sulphur effectively,” added Mr Kerr.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article