Warmer, wetter weather and fewer colder spells is leading to a change in worm patterns in livestock according to a new report which urges farmers to be on their guard against parasites throughout the year.

Data from the Zoetis Parasite Watch Scheme, which is now in its seventh-year monitoring worm egg counts from a network of farms across the country, has found worm patterns to be changing.

In 2021, worm egg counts were low at the start of the year due to the cool, dry spring, yet in 2020, high counts were reported in many areas as early as March.

Last year, worm egg counts peaked from June onwards once the weather became warm and wet, continuing right through the summer months. The highest counts of the year occurred in September and November.

"Worms and their breeding habits are intrinsically linked to the weather because part of their lifecycle is outside the animal. This is why we are seeing a changing pattern to the worm challenge," said Zoetis vet, Ally Anderson.

"Some 20 years ago, it would have been unusual to see worm egg counts peaking in November, but our seasons are less defined now, and our autumn and winters are warmer and wetter.

"Changes in grazing practices, what stock has been brought in and past treatment history can also influence worm burdens on farms," she added.

Eurion Thomas from Techion, the manufacturers of Faecal egg count (FEC) testing kit FECPAKG2, also said there has been a big change to the timing of treatments due to the changing weather patterns.

"Traditionally, farmers would treat stock based on the time of the year, with many still doing this. However, now the risk periods are not so defined, it is vital farmers treat stock based on when they need it. This not only helps ensure the treatments are effective, but also preserves wormers, protects the immediate environment and ensures the growth from animals is maximised, which is vital for farm sustainability and also in reducing emissions from livestock."

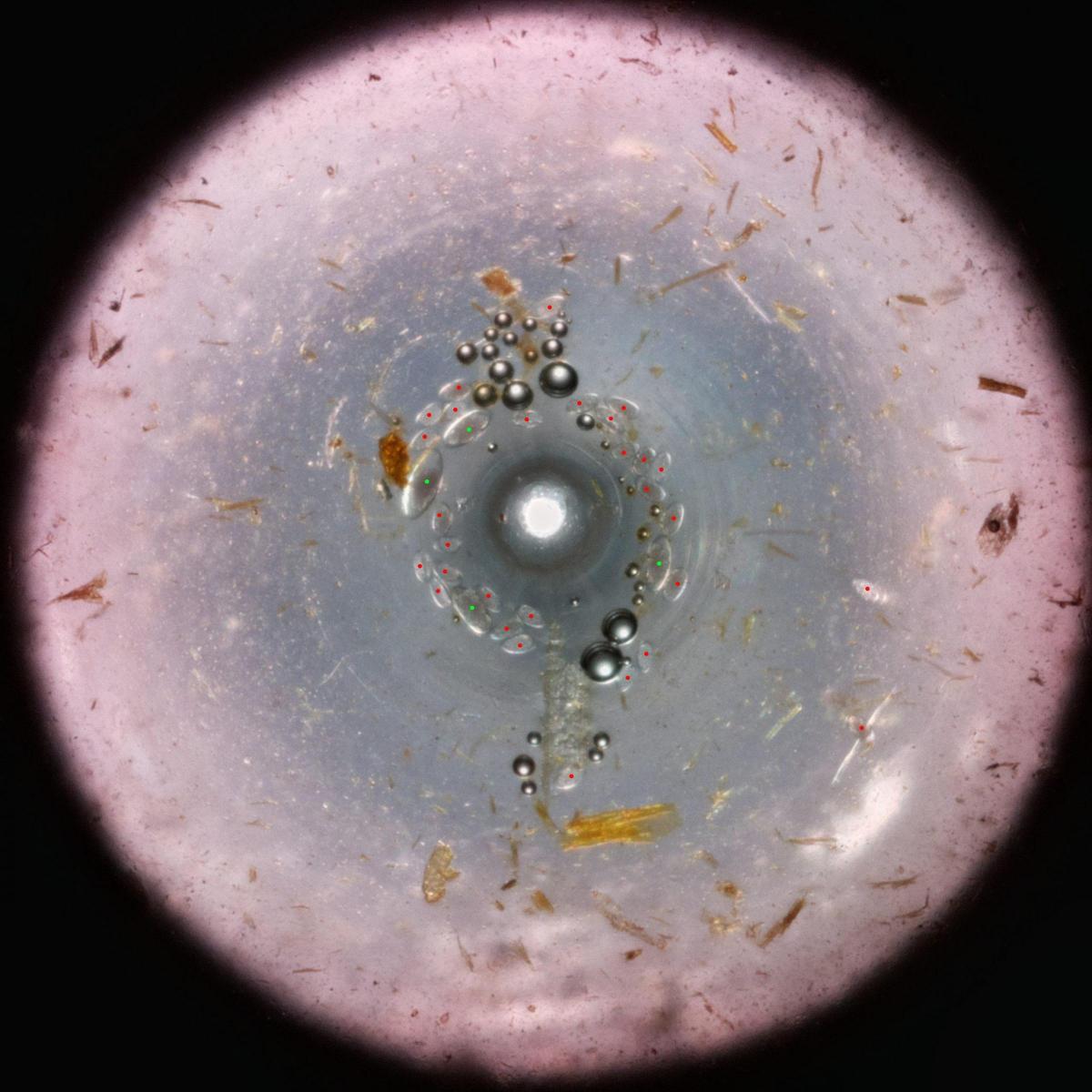

Worming decisions should ideally be based on faecal egg counts (FEC) alongside growth rate data, the body condition score of animals, and a farm's previous parasite history. Test results should also be shared with a vet or animal health advisor, who can help interpret the results and decide on the best treatment.

Mr Thomas added: “FEC tests should be conducted in lambs from six weeks of age when they are out at grass. If test results reveal low worm egg counts and no treatments are given, a further test should be taken two weeks later to make sure nothing is missed.

“This is because FEC tests only detect adult parasites. It can take three weeks from ingestion for the larvae to develop into adults, lay eggs and for those eggs to be excreted back into the environment in the dung. Therefore, lambs should be regularly tested throughout the grazing season,” he said.

He added that the price of faecal egg count tests is money well spent as they can help reduce treatment costs meaning the most suitable wormer can be used when there is a risk, reducing the resistance pressure through unnecessary treatments.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here