Dental pain in horses can go undetected because of a subtlety or absence of clinical signs and many horses will continue eating despite painful dental conditions

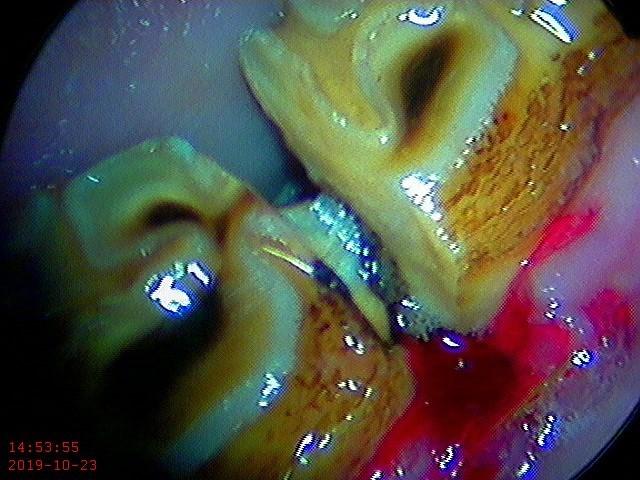

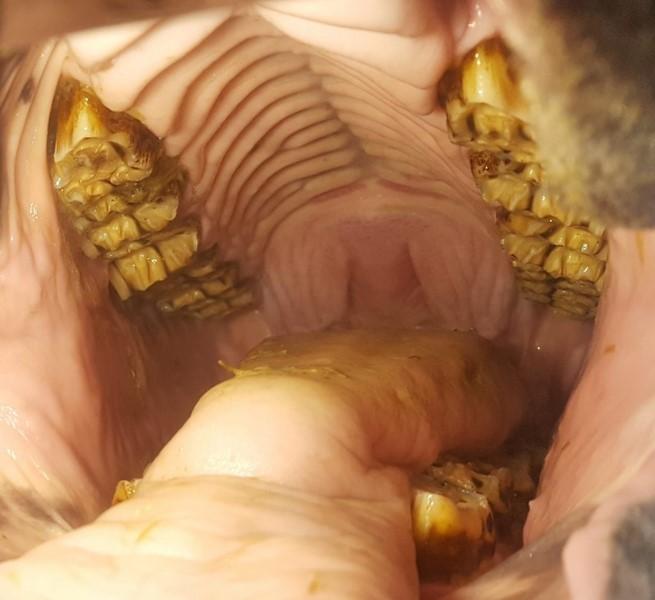

Recently in equine dentistry the use of specially designed cameras (oral endoscopy) allow access into the horse’s mouth and detailed imaging of horse dentition. Use of these cameras has highlighted that oral problems exists at a much higher prevalence than previously reported.

Results from studies using oral endoscopy have shown diastema (pleural: diastemata) is a common dental condition that horses suffer from.

Diastemata are abnormal gaps between the teeth which can occur for a number of different reasons. The gaps allow food to become trapped between the teeth and this packed food causes painful periodontal disease as the soft tissue around the teeth become affected.

The presence of at least one cheek tooth diastema was found in half (50%) of horses in one large study.

Diastemata

These are thought to be one of the most painful oral conditions in horses, because of the pain with the packed food and the associated periodontal disease.

The most common clinical sign of oral pain from diastemata is quidding, the dropping of food whilst eating. Some horses also make odd faces when eating and a smelly mouth and food packing on the inside of the cheeks can also occur.

Diastemata arise for different reasons. Depending of the cause of the diastemata, they are classified as primary, secondary or senile.

Primary diastemata occur when the cheek teeth are not angled together sufficiently or when the teeth have erupted too far apart from each other. This type is often identified in younger horses.

These cheek teeth diastemata carry a better prognosis than diastemata that develop later in life, as the spaces can often close with continued dental eruption.

Secondary diastemata are acquired and develop because of changes within the horse’s mouth during the life of the horse. These diastemata can develop when teeth erupt in the wrong position and/or direction or because of opposite overgrown teeth pressing food down into a gap.

Sometimes extra teeth cause diastemata because they often have irregular positions and edges. Other secondary diastemata cases occur if a tooth is missing because the remaining teeth move to fill the gap. This is seen following extraction or loss of a cheek tooth.

Senile diastemata describe those cases that develop as the teeth age. Prevalence of senile diastemata significantly increases with age. Due to the continuous eruption of horse teeth, the narrower ends of the teeth eventually erupt, and the overall tooth diameter becomes smaller in size resulting in senile diastemata.

Treatment of diastemata

Diastemata can be complicated to treat and should only be carried out by a vet. The first stage of treatment should be identifying the cause.

Corrective equilibration of the cheek teeth is important, which involves addressing any potential overgrown teeth opposite the diastemata or any sharp enamel points.

This simple treatment can provide resolution in many cases. Reducing the surface of the crown immediately adjacent to the diastemata can help to reduce the compression of food into the space.

Cleaning out trapped food from the periodontal pockets and gaps between the teeth is essential to allow healing of the gums. Placement of temporary packing such as dental putty is also commonly used.

A ‘chlorhexidine’ based mouthwash can be useful for cleaning the cleared periodontal pockets; however, it will not be useful for treating periodontal disease caused by diastemata without addressing the food packing itself.

Widening of the space between the teeth, with the aim of opening diastemata can be considered for select cases of valve diastemata where the top of the gap is narrower than the bottom of the gap.

Awareness of how close the living and sensitive pulp of each tooth is to the space is essential when widening the gaps.

Heat damage and pulp exposure are both risks of this procedure and careful visualisation during widening of the diastemata is important, with use of water irrigation.

For this reason, only vets are qualified to carry out this procedure. Dietary modification, substituting long fibre with short fibre and grass can also be reasonably successful, although feeding short fibres will increase vertical chewing actions and the development of sharp enamel points.

In conclusion, some diastemata can be easily resolved, but many need to be managed over time and involve multiple visits to sort out. Horse owners should be aware that these are not ‘one visit’ fixes and repeat treatments and lifetime management is often required.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article