By Alasdair Macnab

I have had, so far, an interesting and varied career as a veterinary surgeon and a farmer...

I have seen a lot of change and progress in animal health and welfare, farming systems and environmental protection, much of it to the good. I will admit, that over these years, I have tended to file away (my better half uses the term hoard here) articles and items that I might want to refer to later. A combination of finding some old magazines recently and discussing future articles prompted the content of this month’s column – the sheep industry’s behaviours and responses to veterinary advice on disease control and management.

At a job interview with DEFRA in 1990 I was quizzed on my opinion on managing and controlling a ‘new’ disease to GB but known for over 200 years called Jaagsiekte or OPA. It had arrived in Britain with sheep imports. It is a very infectious viral disease, which causes tumours in the lungs and progressively reduces their working capacity. To date no treatment or vaccine is available.

My view was, as it wasn’t long since it came into the UK we should be making some effort to control and eradicate it as we knew where the imported sheep were. Nothing ever happened.

Maedi-visna came in about the same time. Initially contained in pedigree flocks and controlled by the Maedi-visna scheme it eventually found its way into the commercial flock and is now widespread in the UK.

A similar story can be heard about CLA which unlike the other two, can infect humans.

Why have we allowed this to happen?

Sheep, as with all living things, are susceptible to diseases. Treatments, vaccines and management systems have evolved to manage most diseases. What is it that prevents the industry from taking action to deal with some of these diseases? This failure allows new diseases to become endemic in the country. Protecting your flock needs a proper on-farm quarantine system coupled with a surveillance programme to monitor the flock’s health.

The word ‘quarantine’ means many things to many people and nothing to many stock-keepers. I’ll borrow a phrase used by vet Matt Colston in another article “We are supposed to be adopting a strict health policy in UK flocks, but in many cases the risks farmers are taking make it look more like biopromiscuity rather than biosecurity”. That is, the industry is paying lip service to disease control.

Recent bravery in the face of my better half’s anti hoarding campaign yielded a rare piece of farming history. A pristine copy of the SAC Sheep/Beef notes dated January 1989. Oh how joy can turn to despair. It starts with a review of the market outlook, quite cheery back then, full of talk about Guide Prices, Commission discussions; then over the page into the vet talk – preventing abortion, Jaagsiekte, liver fluke, next page research and development – breeding better lambs, getting the most from pasture, finishing lambs in autumn and winter, etc, etc.

Pick up (or look up) the same advice today and little has changed. A new disease or two, new authors or two, an odd old author, but the subject matter is still the same. Why is this? Is it advisers who have not moved with the times, or is it the industry which has not moved on? I suggest it is both. But why should this be? That’s another debate for another time.

The sheep trading season is under way, so far reasonably acceptable trade and very acceptable trade for those enjoying top prices at tup sales. The gimmer and cast ewe sales are not far away and many of you will be buying in breeding sheep this year. What else are you buying in and how do you deal with it? The ‘B and Q’ words again. What is ‘biosecurity’ and what is ‘quarantine’?

Biosecurity is a big subject and I shall address that in future columns. I’ll deal with quarantine now as it is of immediate importance to the sheep industry over the next 12 weeks.

Sheep producers continue to underestimate the growing problem of disease, antibiotic and worm resistance when buying in sheep. It’s a big problem and it’s getting worse. Diseases such as footrot, worm resistance, sheep scab, lice, OPA, CLA and Maedi-visna can all be introduced.

Quarantine is the process put in place to identify and manage these problems. It isn’t difficult. It takes a full two weeks in quarantine to achieve the level of health protection required. It requires forward planning of timing of purchases, planning where to put incoming sheep for the quarantine period and what needs to be done to them to protect your business and livelihood.

Worm resistance is one of the more important matters to tackle. How many of you are aware of SCOPS? If you are how many of you apply it? SCOPS is an industry led group that works in the interest of the UK sheep industry. It recognises that, left unchecked, anthelmintic resistance is one of the biggest challenges to the future health and profitability of the sector. The quarantine process you use in your own flock is a matter for you to discuss with your own vet, your best source of advice on controlling sheep disease. Once you have anthelmintic resistance in your flock your options to treat worms and fluke become very limited and it will rapidly affect your ability to make a margin.

Feet are the next problem. Check all incoming sheep as soon as possible after arrival. How many of you have rejected sheep which have foot problems on arrival e.g. tups? How many of you have gone back to the vendor to resolve any problems? Or do you just accept it and hope for the best for fear of offending someone? How many vendors help their customers resolve problems some of which they may not be aware of themselves? Or do they avoid the issue from apathy or fear of repercussion or reputational damage?

Sheep scab has been on the radar for almost all my entire career of 40 years. Despite eradication campaigns with compulsory dipping and now compulsory notification to APHA of suspicion of disease it is still on the go.

Why? Good question. Answer – poor or no quarantine and absence of good biosecurity are the major reasons. Quarantine and treatment is a very effective control. Why is it not practiced across all the industry?

Screening for disease in bought in sheep is a very rare practice. Do you check for CLA, Maedi-visna, and digital dermatitis? Once you see the clinical signs of Maedi-visna about two thirds of your flock will be infected. Why run the risk? Why?

We are facing major planet-wide issues with antibiotic and anthelmintic resistance. I am not understating the case when I say the existence of humanity is at stake, more so potentially than with climate change. It starts with misuse and spreads through apathy and reluctance to address issues directly.

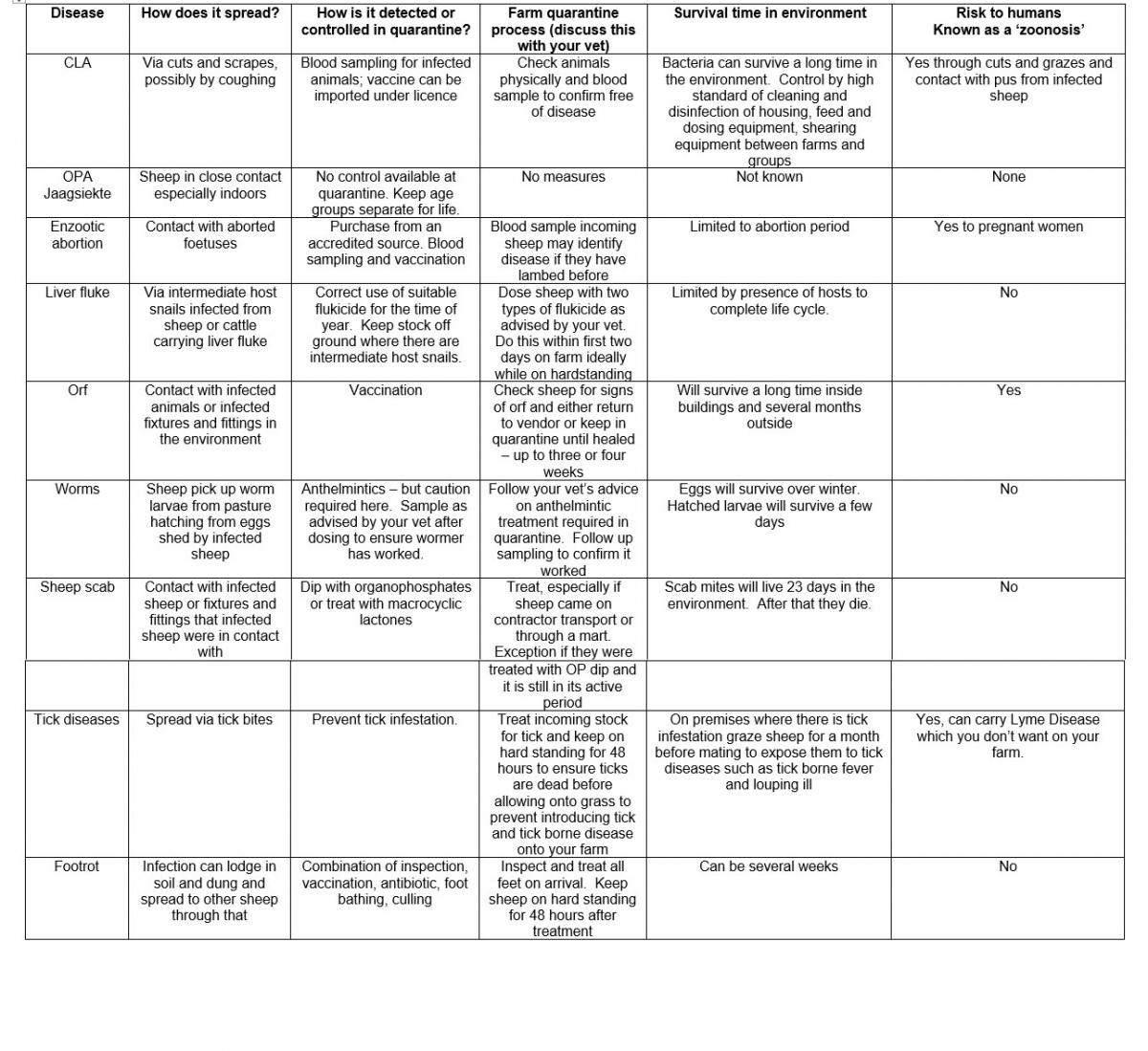

The table attached is a very simple guide on how to use a quarantine system to control disease.

My thanks to Eilidh Corr MRCVS at SAC Vet Services for help in compiling the table. There is a deliberate mistake in the table to test your general knowledge on disease.

If you find the mistake send the answer and your name and address to p.hunter@thesf.co.uk and the winner, selected from the correct answers will receive a bottle of gin.

Answer next month.

Good luck.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here