By Andrew Best of Watson Seeds

One thing that farming is not, is predictable!

It is akin to being a juggler trying to keep all the balls in the air, but in 2018 it was as if there was a hurricane tossing all the balls around.We will not talk about Brexit, but should mention another unpredictable phenomenon, namely the weather, which has probably created more economic uncertainty to individual farm businesses than any other factor this year.

Last year started with winter stocks of forage that were not plentiful, or of good quality, so we were all hoping for an early spring.We are nothing if not optimistic. Unfortunately, the east brought another unwelcome surprise,in the guise of the beast from Siberia. On March 1, temperatures plummeted creating a cold that was amongst the lowest on record.

By the end of the month, the beast returned to the east, to be replaced by heavy rain that was, in places, 110 % of average. We were then looking at soggy fields of unhappy winter cereals, breeding stock in no condition to give birth and the last thing we wanted, a dire shortage of fodder.

More importantly, it was having a detrimental effect on us all, financially and mentally. It would be fair to say that March and April, 2018, are now best forgotten.

Then came the heatwave. Remember the rush to get first cut completed before it rained. Well, it never appeared and by mid-July it was evident that grass production would not be enough to make up for the shortfall. Indeed, some larger dairies were having to consume forage from earlier cuts.

Unfortunately, if grass was not growing it was particularly difficult to get anything else to establish and grow either, with the probable exception of maize, a sun and heat lover that certainly took the pressure off forage on a few farms that had persevered with it. In previous years some would have in practice sown brassicas. but it was found, as usual, Mr Redshank and Mrs Fat Hen preferred the conditions better than the kale and rapes. Forage production from these sources was not looking promising.

When the weather did finally turn more growthy from the middle of July, the race was now on to make up the forage shortfall for the winter. Forage audits – or looking at nearly empty silage pits – all confirmed that feed for the winter was now going to be limited.What were the options to make up for this shortfall? More cuts of grass, or try and grow brassicas?

Unfortunately, time was running out to sow brassicas and certainly by early August, the time for planting anything, apart from stubble turnips, was past. However, as we had discovered, 2018 was not a normal year.

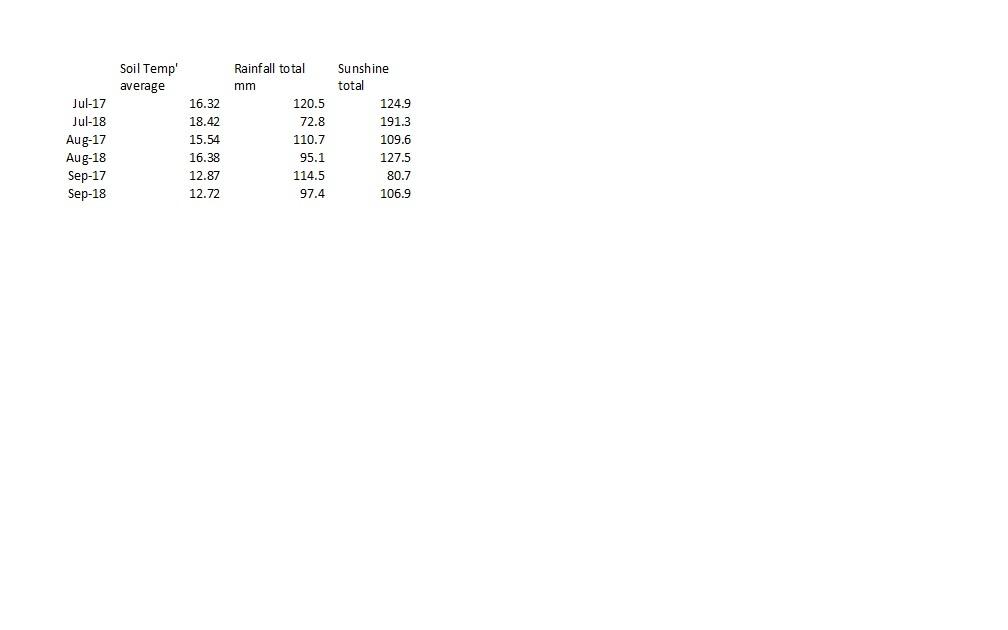

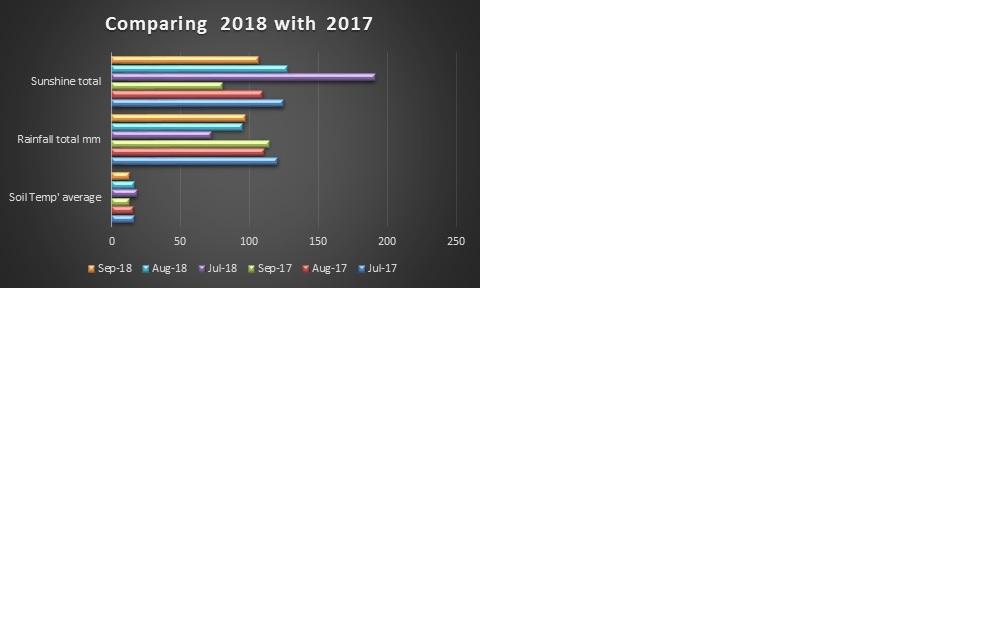

The dry weather from the previous months had dried out the soil more than in any previous year, plus rain and growth conditions were perfect. Wet, warm soil, not saturated as in previous years – in short, it was ideal conditions for growth, especially root development. For example, the weather station at the Crichton Royal, Dumfries, recorded the following soil, sunshine and rainfall records for the months of July, August and September over the years 2017 and 2018. As you would expect, 2018 had a plenty of sunshine, heat and moisture, a contrast to 2017.

A few farmers took the opportunity to acknowledge the potential forage shortfall to plant forage crops for augmenting winter forage stocks.The Biggar family, who farm Chapelton and Grange, at Haugh of Urr, Castle Douglas, with their famous pedigree herds of Beef Shorthorn and Aberdeen-Angus, although technically not worried about forage, as later cuts had been very good, had plans to start renovating old swards into grazing paddocks using brassicas as a method of breaking up the old sod.

Unfortunately, due to the weather, late sowing of brassicas had to be undertaken.Two fields were sown on the August 8 and 9, both of which had never been ploughed in living memory.

In the Townhead field, Italian ryegrass was sown along with the White Star stubble turnip, as an insurance due to the late sowing date for this area. However, conditions certainly suited the White Star stubble turnip, as very little Italian was able to compete.

All the fields were fertilised with 100kg per acre of 20.10.10, followed by nitrogen as a foliar spray, along with insecticides for saw fly (A tleast this pest enjoyed the heatwave!).

Towards the end of November, Jamie Biggar, worked out the carrying capacity of the two fields. The main points for calculating were:

1.Weight of animal as this will determine the dry matter intake.

2.The yield of the field, best to measure a few square metres to get an accurate figure.

3.The type of crop to calculate the dry matter. For example, a stubble turnip will have dry matter of 8%,whilst kale will have a dry matter of 13-14%.

4.It is also essential to feed only 70% of the diet as a brassica, the rest should be a long fibre, such as straw or poorer quality silage. Minerals should also be fed.

The calculation for the Townhead field of stubble turnip and Italian ryegrass for 25 cows was as follows: TABLE!

The yields were higher than expected at about 6-6.5 tonnes DM/ha. The dry matter for the kale is 15% and 12% for the stubble turnips, this works out as 6 to 6.5 tonnes/ha. Assuming a 80% utilisation, this will give 0.5 kg DM per square metre. An animal’s energy requirement is typically 80mj per head per day and assuming 10 ME for crop and silage, with 70% coming from the forage crop, will give 11sq m/cow/day plus 10kg silage at 25% DM.

As a fact, the group was getting access to about 300sqm a day.

Photo of Jamie Biggar in a field of stubble turnip and Italian rye grass.

Another example of seizing an opportunity to grow forage, was demonstrated by Alex Henderson, Dalruscan, Amisfield, Dumfries.

On August 10, he took the opportunity to seed 20 acres of a 39-acre field, which was previously spring barley grown for whole crop silage. The mixture consisted of 2kg Pulsar, forage hybrid and 0.5 kilos of Sampson stubble (per acre). The field was established and costed as follows:

This was a purely opportune crop. The field in question would have been fallow until the spring of 2019, so with the weather and conditions correct, why not plant a crop that could utilise the conditions, despite the late sowing date?

Also, at the same time it would improve the soil structure and utilise any surplus nitrogen. In normal years, the cost of establishment and the lateness of sowing would have made this crop a doubtful prospect for a return on the investment of nearly £70 per acre.

As mentioned, 2018 was not a normal year and Mr Henderson was satisfied that the investment had been recouped with income from lamb finishers from a local farm.

Over on the east of the country, William Fleming and his father, at MossTower, Kelso, assessed their forage stocks and they calculated they would be back 15% to 20% on their winter requirements. This is a 670-acre farm, consisting of 450 acres of arable and the remainder in grass for grazing and silage.

Stockwise, they have 250 spring calving sucklers and 30 autumn calvers. The breeding of these animals is between Limousin and British Blue, and all the off-spring are fattened on the farm using home-produced feed. The bulls are left entire and any heifers not good enough for herd replacements are also fattened and sold through the live ring at Newton St Boswells.

The silage from 2018 analysed well, but unfortunately the quantity was lacking by around 15% -20%.This, combined with a reduction in straw quantity of the same level, meant action was necessary to make up a significant shortfall in the winter forage requirements.

It was decided to double their forage brassica sowing from 30 to 60 acres and on July 27/28, after the winter barley fields were cleared of straw, two varieties of brassicas were sown – thirty acres of Redstart, a hybrid rape/kale, and 30 acres of Gorilla, a new forage rape with higher than average dry matter content and with excellent clubroot resistance.

The sowing rate for both was 2.5kg per acre and to utilise the forage crops to best advantage, William moved the electric fence twice a day. This – considering the weather conditions on some December days when a dry, windproof shed must have seemed much more appealing – proved a bit of a task, but the benefits to the farm business more than compensated for the personal discomfort.

William calculated a saving on silage feeding of £90 day, as well as no bedding costs. Although, to complement the ration, he offered ad-lib straw and calculated a consumption of 6kg of straw per day.

As of January, he calculated that he has enough forage to last him until about now, with the animals doing well – almost too fit, he said. Plus,the ground has been well broken and fertilised, conditioned for the next crop.

Next year, William proposes the same increased acreage of forages. The lessons that can be learned from these three farmers is flexibility, being able to adapt to current circumstances and be prepared to take a chance, plus planning for winter feed requirements. However, no two years are the same climatically and who knows what 2019 will bring!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here