By Tony Waterhouse SRUC

The idea of building a ‘virtual fence’ by combining a ‘sat-nav’ for cows with an ‘electric fence collar’ has been around for more than 20 years.

These ideas have moved from science fiction towards a practical reality through a combination of technological advances and research and development work around the world.

The idea may sound simple, but requires a sophisticated combination of solutions. Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) is amongst the institutions to have carried out research on evolving systems.

There are two commercial products building upon all this work that are now available to the farming industry for cattle in Australia and for commercial goat farming in Norway (Agersens with eShepherd in Australia and Nofence in Norway, which says there will be cattle system available soon).

The different technical elements that have come together all start with GPS units found in every mobile phone. These are cheap and reliable and are the core technology for auto-steer in agricultural equipment, car sat-navs and a host of personal mapping apps on mobiles.

A major challenge that is being overcome is how to get information between the animal-based GPS unit and the user. This is not least a problem in rural areas, not blessed with good broadband and mobile phone coverage.

The companies mentioned above have each used the two alternative approaches. Nofence uses mobile phone technology to communicate from animal to user and from user to animal. Eshepherd is using a new Internet-of-Things (IoT) technology commonly called LoRa, a low power radio system.

SRUC has had a LoRa network running at its Kirkton research farm for two years, tracking livestock in real-time, and collecting information from a host of land-based sensors.

The collar on the animal carries the GPS controller unit, communications and batteries, plus the most sensitive issue about virtual fencing. A low-power rated electric charge is used as the ultimate controller, using much lower charge than standard electric fences, but critically using warning or guidance sounds in the buffer zone near to the virtual fence.

Research at SRUC has shown that cattle very quickly learn about the sounds and electrical stimuli and almost immediately respond to the sound alone to identify where the invisible fence lies. SRUC used a partially-virtual system which uses buried wire to create the barrier, ‘bouncing’ a signal via induction current and with no contact to a collar and controlling unit.

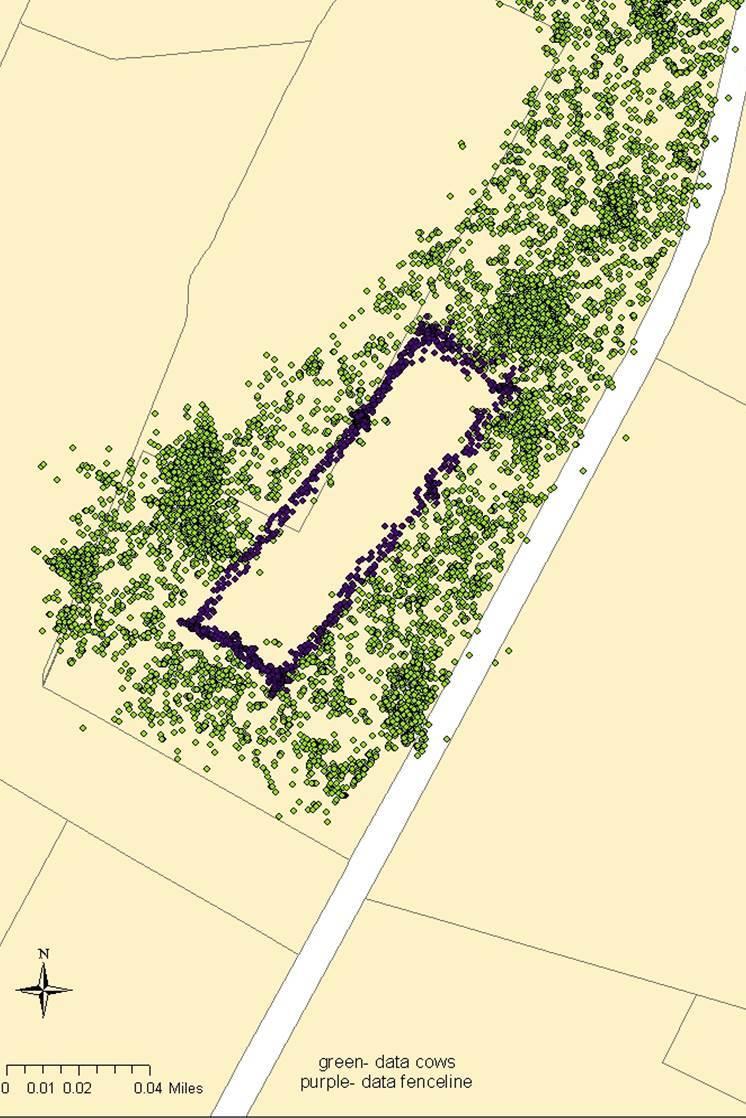

Within a carefully controlled experiment, a new ‘invisible fenced’ area was set up in a field and turned on and using GPS tracking collars cattle movements were recorded along with observations. Almost 100% success was found with the collar, with the cattle using the warning sound alone to stop as they approached the virtual line.

However, there is no getting away from the sensitive subject of the electrical stimuli in the collar of virtual fences. In an ideal world, warning sounds could link to other irritable sounds to manage the stock, but while SRUC work has shown that these can influence livestock movement, it is only to a degree.

Battery power is still a limiting factor, but smart programming in the units can reduce power need, with a ‘season’s-worth’ of power the spec' that farmers want. There are many people and pet-tracking systems which depend on frequent re-charging, but this is not an option up on a hill.

The Australian units use solar power to top-up batteries – a great idea, but will these work in Scotland?

The sophisticated part of the controller needs to consider both animal welfare and efficacy. The unit can have fail-safes to stop multiple contacts, the fence line can be one-way so animals can return after breaching the invisible barrier and there are other 'smart' ways to help the animal make sense of the system.

Research and demonstration trials has led much discussion of how these systems might be used, not simply as a like-for-like alternative to permanent fences or electric fences, but as a more flexible approach to livestock control.

A new term, ‘virtual herding’, has also appeared. There is much potential in what farmers will hold in their hand, or in the farm office. Maps with dots for cattle location, alerts about fence breaches, other information about animal behaviour can all come to the screen as part of an app. Ranchers in Australia and hill farmers in the UK are equally interested in opportunities to move the stock around virtual paddocks. A steadily moving fence-line can also gather stock, automatically bringing cattle to the handling paddock over a few days and with any ‘stragglers’ showing up as dots on a map has obvious benefits.

In the UK, early-adopters might want to control stock for more specialist needs. These might include where physical fences are just not an option, keeping stock away from water edges, temporarily away from conservation-protected zones where physical fences are not practical, or where public visitor numbers are high.

Virtual fencing is likely to be on its way to the UK soon, through export sales from existing manufacturers or for home-based innovation.

So, instead of ‘can it really work?’ the questions will soon move to ‘will it work in my situation?’ and ‘is it affordable?’. Time and experience will tell.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here