Jaagsiekte or ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma (OPA) has been around for decades and while there still remains no vaccine, or cure for this debilitating cancer which affects all sheep breeds, it is at last becoming more recognised.

At one stage such was the reputation of this sinister condition – which shows similar clinical symptoms to chronic pneumonia – that flockmasters never talked about it outwith the farm for fear of losing potential sales.

Even yet, sheep farmers of various breeds will deny all knowledge of it.

However, while the disease remains a challenge to scientists and sheep farmers, getting an actual grip of how widespread the virus is in Scotland and south of the Border, is also impossible to quantify, according to the scientists and pathologists at SRUC and the Moredun.

Speaking at an SAC Consulting webinar, Heather Stevenson, of the SRUC Veterinary Services, Dumfries, said the only evidence they had was from three different types of surveys with the national prevalence still unknown.

“In 2008, 12% of the 125 sheep farmers in Scotland surveyed said they had OPA in their flocks, while a fallen stock company survey in 2012/2013 of 106 sheep found the disease in 5.6% of them,” said Ms Stevenson.

“In 2014, the lungs of 3385 cull ewes were tested for the disease at an abattoir in Birmingham which found just 0.9% of the sheep with the condition, which does seem low, but then the sheep were obviously fit to travel all the way south.” The project was funded by the University Innovation Funded OPA-NET Scotland.

She added that each year, between 60 and 85 cases were diagnosed in veterinary labs in Scotland, England, and Wales, which she admitted is likely to be an underestimate when few sheep deaths are actually investigated.

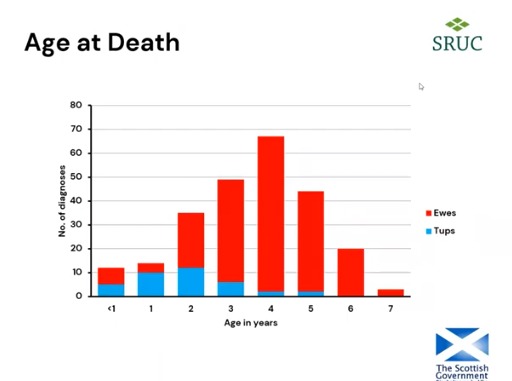

Age of animals with OPA in males and female sheep

Known as a significant production limiting disease in many countries of the world, including the UK, the visible symptoms of OPA include deep, heavy breathing, loss of condition, inability to keep up with the flock and coughing.

However, these clinical signs are only the tip of the problem, with many subclinically infected individuals within the flock.

According to SRUC, losses can be as high as 20% within the first few years when the disease is first identified in a flock, with ongoing losses then estimated to be around 1-5% per year.

Affected animals most commonly show signs of disease at three to four years of age, but the condition is occasionally identified in lambs as young as two months old. Once clinical signs develop, affected sheep die within days to months.

In addition to mortality, production losses such as increased ewe barren rate and reduced lamb weight gains are likely because of poor ewe body condition. The impact of this has not yet been quantified and the true economic cost of the disease is unknown.

In more recent years, ultra-sound scanning techniques to identify infected animals, have allowed individual flockmasters to get a grip of how prevalent the disease is within their units.

While the test is not 100% accurate, it can identify those with the biggest tumours which can, therefore, be culled when they are still of value and before the shed excessive amounts of virus to the remainder of the flock.

But, ultrasound scanning can only detect tumours of more than 1cm in size in the ventral areas of the lungs, according to Dr Chris Cousens, of the Moredun, who has been studying the disease for almost 30 years.

She said: "False positives can also be identified at scanning with a recent study of 12 farms showing that 4% with positive ultrasound scans did not in fact have OPA, but had other lung disease instead.

“In the hands of an experienced scanner, the number of false positives are minimal and if required a rescan of certain cases may be advised."

Furthermore, she added that a negative result is not a guaranteed absence of OPA in individual animals.

Both sides of the chest need to be scanned as tumours can be present in only one lung. Speed of progression is highly variable, but in some cases, small tumours can grow to a large size within three months.

It is recommended that any sheep with suspicious lesions at scanning are quarantined and scanned again two months later.

Regular scanning at 6-12-month intervals with prompt culling of all positive sheep can be used as an OPA risk reduction strategy.

Experienced veterinary surgeons can scan up to 120 adult sheep per hour, but 60 to 80 is more realistic. Typical fees are £1 to £2 per head

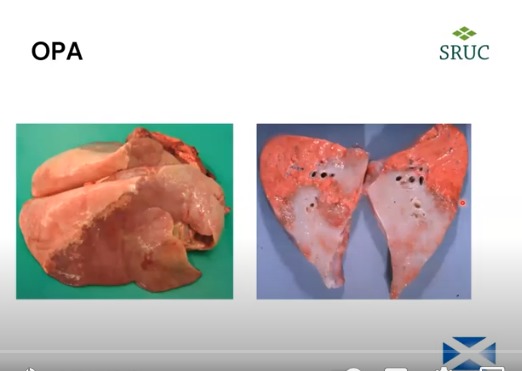

Two photographs both tumours in the lungs - indicitive of OPA

Transmission

The Jaagsiekte virus (JSRV) is found in the fluid from the lungs of infected sheep and is mainly transmitted through the air by inhaling infective respiratory droplets.

Close contact such as housing, trough feeding and even feed blocks provides ideal conditions for the virus to spread. It can also be transmitted from ewe to lamb via milk or colostrum.

It is thought that sheep with advanced OPA tumours pose the greatest risk for JSRV transmission, but Jaagsiekte affected sheep will also be able to transmit the virus before showing clinical symptoms

What is more confusing is the fact that not all JSRV infected sheep go on to show clinical symptoms and not all go on to develop tumours.

“In one flock in Italy with 2-3% animal losses per year, it was estimated that up to 30% of the flock were virus positive without showing any signs of the disease,” said Ms Stevenson.

More worrying is the fact that Dr Cousens believes this figure could be a lot higher and nearer 70% going by a three-year study published as a PhD thesis

Young lambs are most susceptible and the time between infection and clinical signs developing is dependent on age and the dose of JSRV.

Clinical signs of disease

1, Progressive weight loss, despite normal appetite.

2, Increased cases of pneumonia in adult animals that fail to respond to antibiotics.

3, Secondary bacterial infections and other concurrent infections of the lung are common.

4, Normal temperature unless there is also a bacterial infection.

5, Increased number of ‘sudden’ deaths.

5, Although these deaths appear sudden, the lung tumours may have been present for months to years.

These are usually a result of Pasteurella pneumonia and affected sheep can be in good body condition at the time of death.

6, Animals seen lagging behind the flock when gathered or handled.

7, Animals struggling to breathe (flared nostrils and increased breathing rate) particularly after exercise.

In around two thirds of advanced cases, fluid can be seen running out of the animal’s nostrils when the head is lowered.

8, 10-40 ml per day of frothy, clear or at times pinkish fluid/mucus is common but this can be up to 400 ml per day. Around one third of cases don’t produce any fluid.

9, Cases peak in January and February due to affected sheep being unable to cope with adverse weather conditions and nutritional restrictions at that time of year.

Deaths can occurs days to months after clinical signs are first seen.

Diagnosis

The identification of fluid coming from an animal’s nostrils following the ‘wheelbarrow test – raising the hind limbs and lowering the head to check whether or not fluid will flow from the nostrils – is diagnostic for OPA, although use of this test is no longer advised because of the stress to the animal.

However, if no fluid is seen then diagnosis can be challenging as ill-thrift is a feature of many other diseases of sheep.

There is no commercially available laboratory test for the diagnosis of OPA in live animals. A PCR test has been used in research studies, but it lacks the sensitivity for field diagnosis in individual animals.

The gold standard for OPA diagnosis is post-mortem examination followed by histopathology. OPA affected lungs are enlarged, heavy, oedematous and fail to collapse.

Control and prevention

The purchase of clinically healthy but infected replacement animals is the biggest risk factor for the introduction of OPA.

Ideally, a closed flock should be maintained and stock tups should be purchased from trusted sources that have scanned their whole flock and have a low prevalence of OPA.

Once introduced to flocks for the first time, JRSV can spread quickly and high numbers of individuals can subsequently succumb to OPA.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here