Despite a late start to the strike season following a cool May, warmer temperatures in June and high levels of rainfall in certain areas have made for perfect conditions for large numbers of blowfly to emerge.

According to professor Richard Wall from Bristol University, 2021 saw a late start to the strike-season, however, high levels of rainfall have made fully fleeced sheep more susceptible, meaning that those flies that did emerge early were able to find suitable sites to lay their eggs.

"Warming temperatures mean that blowflies are starting to emerge in larger numbers and so the numbers of strikes will start to increase. Preparation for strike prevention is now essential," he said.

Blowfly strike results from the opportunistic invasion of living tissue by the larvae of Lucilia sericata (greenbottle flies), Phormia terraenovae (blackbottle flies) and Calliphora erythrocephala (bluebottle flies). Primary flies such as greenbottles initiate strike on living sheep with soiled fleece or wounds, while secondary flies such as bluebottles and blackbottles only attack areas which are already struck or damaged.

Populations are greatest during the summer months, although due to changes in climate the risk period can be from March to December in some lowland areas. The entire life cycle from egg to adult can occur in less than 10 days in optimal conditions.

A major economic concern for farmers, blowfly strike requires considerable prevention costs for all at-risk sheep. Sheep affected with blowfly strike have disrupted grazing patterns and rapidly lose weight especially if untreated for several days.

Adult female flies deposit eggs on dead animals or soiled fleeces and eggs hatch into first stage larvae within about 12 hours. These larvae feed on skin and faecal material, becoming mature third-stage maggots in as little as three days if temperature and humidity are at optimum levels. Third-stage maggots then drop to the ground and pupate; mature flies emerge after three to seven days between May and September. Flies can over-winter in the soil as pupae and emerge as soil temperatures rise during the spring.

Maggots are active and feed voraciously, causing skin and muscle damage by secreting enzymes. Secondary blowflies are attracted by the smell of decomposing tissue. Toxins released by damaged tissues and ammonia secreted by the maggots are absorbed through the lesions into the sheep’s bloodstream, causing illness and death in severe cases. Secondary bacterial infections are common and may also cause death if untreated.

A major animal welfare concern, strike will affect an average of 1.5% of ewes and 3% of lambs in the UK each year, despite preventative measures undertaken by most farmers. These numbers will be much higher too if no control measures are adopted. At least 75% of sheep farms report cases of blowfly strike each year.

Flystrike also affects the feet, with foot lesions causing severe non-weight bearing lameness, compounding the welfare implications of lameness alone. Death can result in neglected cases, with mortality associated with fly strike estimated at 5% of affected animals.

Unlike the situation for sheep scab and lice, most of the blowfly lifecycle occurs off the sheep and adult flies can travel large distances between farms.

Clinical signs

Adults flies are attracted to areas of soiled fleece surrounding the tail or breech, and less commonly to wounds, footrot lesions, lumpy wool lesions on the skin, and urine scalding around the prepuce. The main clinical signs include:

Isolation from the flock

Discoloured wool

Agitation and kicking or nibbling at the affected area

Disturbed grazing

Tissue decay

Toxaemia

Death

Blowfly strike lesions may range from small areas of skin irritation with a few maggots to extensive areas of traumatised and devitalised skin resulting in death of the sheep. Most commonly the back end of the sheep will be affected, but lesions may also be seen over the withers, back, shoulders and head.

It is a legal requirement to inspect all sheep daily during the highest risk periods for signs of blowfly strike; disease is easily detected by observing sheep whilst grazing. Gathering sheep into a group with dogs will obscure this abnormal behaviour, meaning that early signs of disease may be missed.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on visual inspection: large numbers of adult flies are seen on the discoloured fleece with maggots on the blackened skin once the surrounding fleece has been lifted clear. There is an associated putrid smell. Skin which has been previously damaged by flystrike may grow black wool.

Treatment

Treatment of individual affected sheep involves physical removal of maggots, cleaning and disinfection of wounds and supportive treatment such as antibiotics, fluids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) under direction from your vet.

Treatment by plunge dipping using an organophosphate preparation may be undertaken but it is more usual to treat individual animals with dip wash applied directly to the struck area after first clipping away overlying wool.

Prevention and control

Prevention of blowfly strike is an integral part of your veterinary flock health plan. The main costs of blowfly strike are associated with prevention of disease; frequent inspection of sheep coupled with labour-intensive preventative treatments usually cost more than treating a few affected animals, however failure to protect the flock is a major welfare risk and could result in a serious disease outbreak.

There are various strategies that can be employed to reduce the risk of blowfly strike in the flock:

Use of the NADIS blowfly alert to identify the periods of highest risk and take preventative action.

Shearing ewes prior to the onset of the high-risk period

Control of parasitic gastroenteritis caused by roundworms in lambs to reduce diarrhoea and therefore faecal contamination of the fleece

Dagging or crutching of fleece around the tail area to reduce fleece soiling

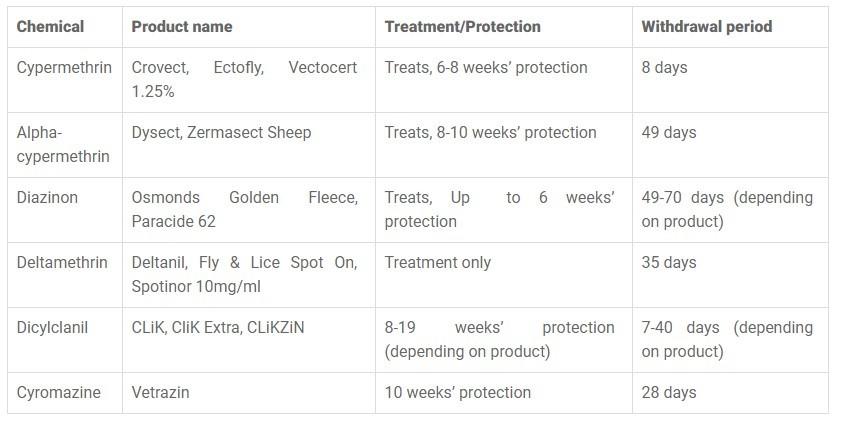

Dipping or use of pour-on chemical formulations to prevent strike or inhibit larval growth

Correct disposal of carcases in order to minimise suitable areas for flies to lay eggs

Ensure all wounds and footrot lesions are treated promptly

Trapping flies to help reduce overall fly populations - this must be used in conjunction with other control methods.

It is vital to adhere to all datasheet instructions regarding application, disposal and withdrawal periods associated with dips and pour-on products.

* It should be noted that the use of dipping to prevent blowfly strike may also help to treat or prevent infestation with sheep scab and lice, reducing the need to use injectable products against these infections.

NADIS, in collaboration with Elanco, have also once again launched the blowfly risk alert to help farmers and prescribers keep up-to-date and stay aware of the blowfly challenge throughout the season. Elanco encourages farmers and prescribers to report a case of strike on the blowfly tracker to help others be aware of the risk in their local area and across the country.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here