PROTECTING GLOBAL soil health is the one major step countries worldwide should be taking if they are to tackle climate change, food insecurity, water insecurity and biodiversity.

This was the take home message during a COP26 event titled ‘Restoring the health of the world’s soil at scale and on time’ which heard from some of the world’s leading scientists working within soil research, who pinpointed farmers as critical vehicles for change within this area.

Read more: Soil health: Soil Essentials helps Beatties get it right

Panellists argued that in previous years, modern agriculture has been geared towards increasing yields to tackle food insecurity, but little consideration has been given to sustainably farming the land and attention given to what lies beneath.

Professor John Crawford from the University of Glasgow – previously Science Director at Rothamsted Research – pointed out that there is three times more carbon in our soils than in the atmosphere, yet discussions on soil health have been largely missing from the main agenda at COP26.

“If you add up all the trees, plants, forests and atmosphere together, that is still only about two thirds of all the carbon that there is in the soil – soil is a very important regulator of climate,” he said.

“Pretty much everywhere that we farm soil, we do it in an unsustainable way and starve it of its carbon. Modern agriculture did an amazing job in feeding everybody and almost eliminating hunger but that was at a time when we didn’t fully understand how everything is connected in nature, so we focused on yield and what happened above the ground,” he continued.

“If we can fix our soils, we can get more carbon moving through the system generating lots of benefits whilst also targeting some of the most profound challenges we have in terms of climate change and the biodiversity crisis.

Read more: Poor soil health is a national security threat

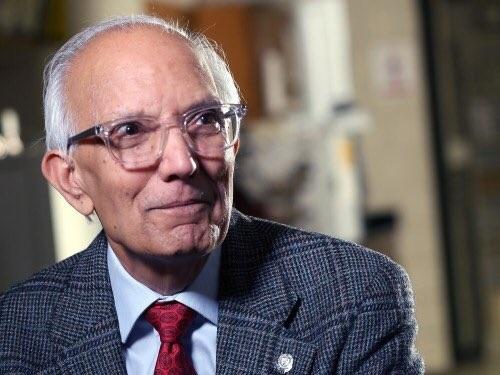

Delegates heard from Professor Rattan Dal, one of the world’s leading scientists on soil carbon and health, who last year won the world food prize.

His presentation titled ‘Protecting the soil and managing the fragile living skin of the earth’ explored what actions can be taken to feed a growing population set to reach 10 billion by 2050, whilst reversing soil degradation and restoring nature loss.

“The green revolution saved hundreds of millions from starvation and was an agricultural success story, but we have been left with degraded soils, polluted waters, aggravated global warming, dwindling biodiversity and denuded landscapes,” he began.

“We need to move from a system of depleting, destroying, degrading, discarding and dominating the land to one that reduces, reuses, recycles, regenerates and restores land to nature.”

He went on to explain that between 1961 and 2020, nitrogen fertiliser inputs worldwide increased 10-fold and that global food systems now account for 20% of all greenhouse gas emissions.

Acknowledging that a balance has to be struck between feeding a growing global population and restoring soils and nature loss, he called for ‘eco-intensification’ of the land.

“We need to increase production from existing land whilst restoring soils,” he explained. “We also need to reduce harvest losses in developing countries which right now range between 10 and 40% and we need to minimise food waste from farm to fork to landfill in developed countries, which is as high as 40%.”

Some other actions which he identified included the uptake of artificial intelligence and precision agriculture techniques, reducing the diversion of food to biofuels – highlighting the example that in the US one third of all corn is grown for biofuels – as well as encouraging a shift towards plant-based diets 'as much as possible'.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here