Kissing spines, also known as dorsal spinous process (DSP) impingement or over-riding dorsal spinous processes, is a cause of back pain, poor or reduced performance and occasionally low-grade lameness in horses.

It can, however, be present in many horses without any clinical symptoms. This article aims to give a review of the current thinking on the condition.

The horse’s back is composed of an average of eighteen thoracic vertebrae (however horses can have an increased or reduced number than this), six lumbar vertebrae in front of the pelvis and in the region of the pelvis five fused sacral vertebrae.

Each of these vertebrae has a DSP which arise from the body of the vertebrae and point upwards. (The body protects the spinal cord). When you feel the horse’s back it is the DSP that are palpable along the midline.

The DSPs range in their height from 2-3 inches up to 9 inches in height, dependant on the area of the spine. It is thought that there should be approximately 3-6mm gap in normal horses between the summits (the top) of these DSPs. This gap is gap is filled with a strong interspinous ligament. There is also an additional ligament which runs along the summits of the DSPs called the supraspinatous ligament.

Horses suffering from kissing spinous processes have a situation where the summits of the vertebrae are closer than normal. This causes reaction in the adjacent processes and damage to the intraspinous ligament.

The site of the damage is virtually always in the seat of saddle area, often around the fifteenth thoracic dorsal spinous process. In some of these cases, there is also concurrent damage to the joints (or facets) of the vertebrae, associated with the body. Kissing spinous processes seems to occur more commonly in Thoroughbreds than any other breed.

What symptoms might we expect with horses with kissing spinous processes?

The most consistent finding is poor performance. This can be manifest as horses jumping poorly, reluctance to jump, lack of impulsion and drive, and mild hindlimb lameness. Some horses (but not all) will show signs of back pain, others may show a difficulty or reluctance in being saddled and occasionally rearing and bucking.

If the horse has had this for a long period of time then they may loose some of the topline (the muscles either side of the spine). The horses must be assessed by a vet to determine whether the afore mentioned signs are related to hindlimb lameness.

It is currently fashionable to diagnose kissing spines, but many of the horses presented with signs as described earlier are lame behind often due to common hindlimb conditions, such as bone spavin, suspensory desmitis or stifle joint pain.

How is the diagnosis made? The horse should be thoroughly assessed at all gaits and when ridden. All causes of hindlimb lameness should be eliminated prior to a diagnosis of kissing spines being made. A basis based solely on just palpation and resentment of manipulation of the horse’s back will often give erroneous results.

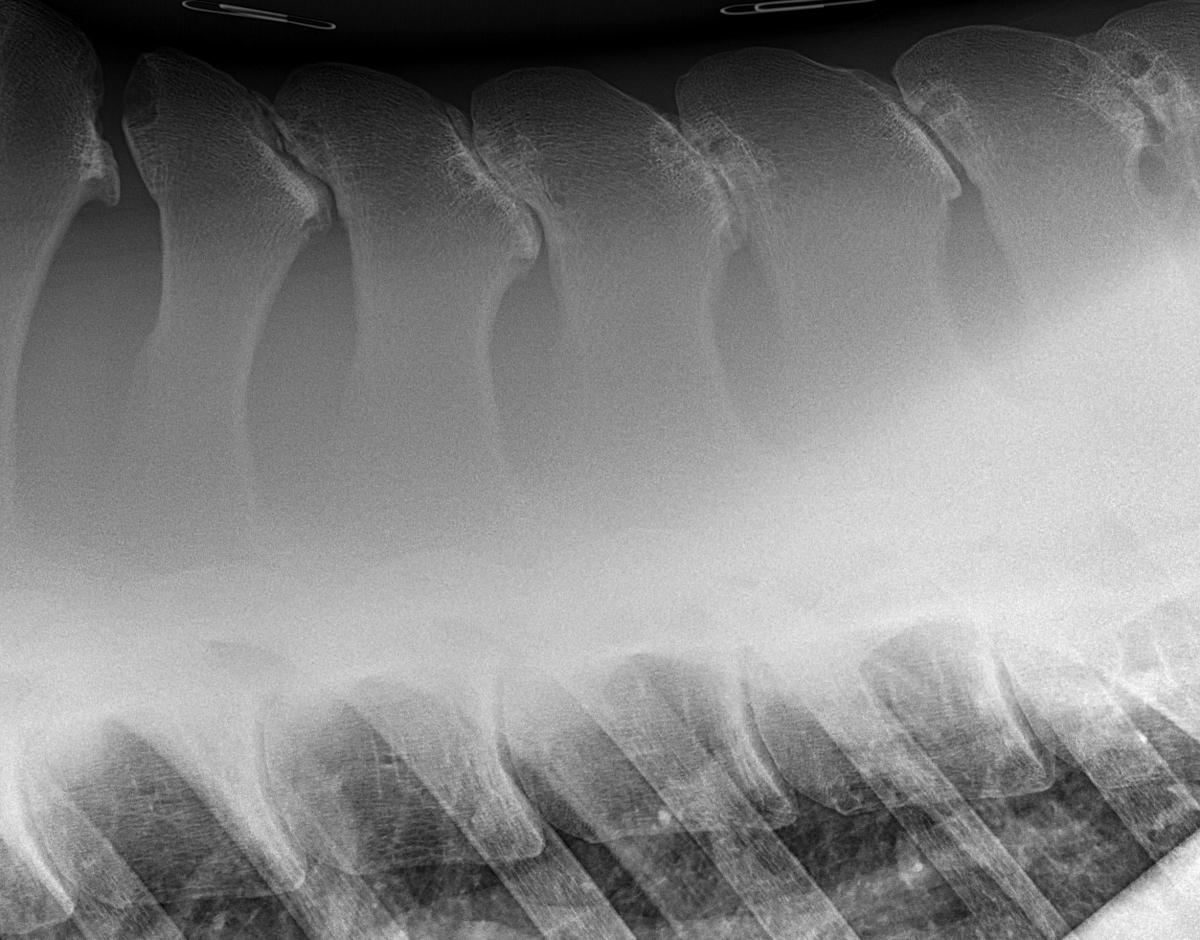

Radiographs should be undertaken and there are typical features which may be found (see Fig1). It should be noted, however, that the presence of abnormal radiographic findings does not always mean the horse is actively suffering from kissing spines and therefore it is preferable for a nuclear scintigraphy (bone scan) assessment to be undertaken.

With this in place it can determine whether there is any concurrent articular facet pathology as well. The radiographic features and response can be confirmed by the vet applying local anaesthetic around the affected area and seeing if the horse’s performance is altered.

Treatment options

Broadly speaking, there are two treatment options for the condition, surgery or non-surgery.

In either case it is important that the horse’s topline is built up to support the bony column. Some horses will respond to an injection of anti-inflammatory medication around the kissing spines; this is usually in the form of long acting depository steroids. With this medication in place horses are able to undergo physiotherapy and exercise modification which builds up the topline.

In unresponsive or severe cases surgery is currently the only known treatment option. There are two surgeries commonly performed, one is to transect through the kissing spines space by incising through the interspinous ligament and the other option is to remove the entire summit (resection of the DSP’s). Both have a variable response and are often dependant on how chronic the situation is at the diagnosis.

In summary, a diagnosis of kissing spines must be based on a thorough examination of the horse at assessment of all gaits and should not be based on palpation and, if possible, radiographs alone.

Treatment options are varied but may involve surgery. If you have a horse you suspect might have kissing spines please consult your veterinary surgeon.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article