Contract farming can offer new entrants to agriculture better opportunities with greater transparency, flexibility, sustainability and lower risk than more traditional occupancy structures, including many traditional tenancies.

They can also allow existing businesses to spread their overhead costs, such as labour and machinery, over a larger agricultural production base without the need for capital to fund the purchase of livestock, land, or to pay rent.

Farmers get the opportunity to take active control of the farming business and the land, whilst contracting out the day-to-day tasks (and often the need for machinery, too) to a contractor who is engaged and invested in farming the land well.

Contract farming can take many forms and this flexibility is one of many attractions to this sort of business structure. However, this also makes it more difficult to generalise on what it means for a particular farm or business.

That said, the typical common features for contract farming agreements whether livestock, arable or mixed can be summed up by the following, prefaced with the word ‘usually’:

Farmer:

Provides land

Provides finance (working capital)

Owns/provides breeding livestock

Runs the books for the business and signs off all expenditure

All farming income comes into farmer’s account

Provides strategic management for the business

Has no guaranteed return from farming and is the ‘at risk’ party in the arrangement

Is not a landlord in the context of the contract farming arrangement.

Contractor:

Provides all labour for day-to-day running of the farming business (though this can sometimes be sub-contracted)

Provides machinery and equipment (this can also be partly sub-contracted)

Contributes to planning farm policy with the farmer

Is paid a basic contracting charge for services, whether the business makes a profit or not

Is usually paid a profit share bonus if the business makes a profit

Is not a tenant, at least not in the context of the contract farming agreement

The case for contract farming is done no favours by a number of largely historic arrangements being dressed up as contract farming by unscrupulous/incompetent agents or advisers which are in fact not contract farming agreements in the true sense, and are actually a form of tenancy in disguise.

This sort of arrangement is, thankfully, becoming more rare, which is just as well as it generally fails to achieve anything meaningful, and carries a lot of risk for both parties. It also reinforces the importance of getting the right contractor, with the right farmer, and the right advice to end up with a properly contracted and managed contract farming agreement, so that it helps both parties achieve their objectives and eliminate avoidable pitfalls.

When structured correctly, a contract farming arrangement can work really well and as referenced earlier in the article this is particularly the case for young farmers and new entrants.

A good example of this would be at Jamie Graham’s Gartincaber Farm, near Drymen, an upland and hill beef and sheep unit.

This is where young farmer, Perry McNickle and his wife, Lorna, have been the contractors in a contract farming agreement since October, 2018.

Perry, an ambitious and capable former shepherd and stockman along with equally capable wife and partner, Lorna, were looking to progress further in their farming careers and take on more responsibility and run his own business.

At the same time, Jamie Graham was looking for a new contractor to take on the running of the business at Gartincaber, which has 60 hill cows, 90 upland cows, 700 Blackface hill ewes, 500 in-bye Blackface ewes and 200 Mule ewes.

The farm is actually three separate, contiguous units of Moorpark, Creityhall and Gartincaber, with a good mix of pure hill ground, some rough grazing parks and in-bye grassland.

The hill cows are mainly based at Creityhall and are mainly first cross Highland cross Shorthorns which are served by Simmental bulls to produce suckled calves and replacements for the upland sucklers. The upland sucklers are mainly based at Gartincaber and are run with Charolais bulls to produce quality suckled calves to Scottish beef finishers.

The hill ewes are on the hill at Moorpark and are run pure to produce fat and store lambs and replacements for both flocks. The in-bye Blackies are run with BF Leicester tups to produce health accredited Scotch Mule ewe lambs, whilst the fledgling Mule flock are served with Texel terminal sires.

For lambing 2020, Jamie and Perry are also trying a Charolais tup on some ewe hoggs to increase production and efficiency, and hopefully profit!

Whilst overall land management policy, grassland and crop management, reseeding, and soil fertility are the responsibility of Jamie, in consultation with Perry and Lorna as the contractors, the majority of the one-off tasks requiring significant machinery resources such as reseeding, silage making and muck spreading are carried out by third party machinery contractors.

These are charged to the contract account, further reducing the need for Perry and Lorna to invest in expensive machinery and equipment.

Although only in his first year of the contract, Perry and Lorna – in collaboration with Jamie – managed to both reduce the cost of purchased feeds and bedding, as well as increase the number and value of lambs and calves sold, no mean feat in the first year of running a new farm.

Overall it’s looking like the farm profitability will increase on the previous year by around £30,000, which Perry and Lorna will directly benefit from as part of the profit performance bonus structure in the contract.

There is no doubt that taking on a farming operation of this scale is a big ask for anyone, never mind a new entrant to agriculture.

The structure of the contract agreement made it much more achievable for Perry and Lorna, as they had to finance the purchase of a tractor, a quad bike and smaller items of machinery and equipment. For a young couple starting out in their farming careers with two young sons to look after, this investment was significant of itself.

Perry observed that it was unfortunate and slightly short-sighted of the Scottish Government’s new entrant start up grants to exclude people like him from the scheme, whilst at the same time providing funding to sons and daughters taking part in a succession process within family businesses.

This is perhaps an area which could be improved upon in future schemes to assist new entrants into the industry, he argued.

Nevertheless, between savings, help from family and a signed contract from Jamie with a guaranteed income for contract services, Perry and Lorna were able to finance the purchase of the equipment they needed to go farming at Gartincaber.

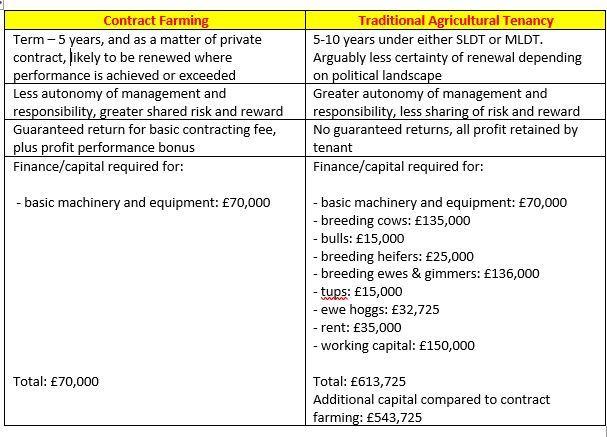

It is interesting and informative to compare the opportunity provided by contract farming at Gartincaber for a new entrant, as compared with a more traditional structure, such as an agricultural tenancy:

As can be seen (table below), it would take additional capital of £543,725 for Perry and Lorna to have been able to set up as agricultural tenants on a farm of this scale, an unachievable target for anyone without significant backing.

What Jamie

Graham thinks:

What attracted you to contract farming?

The ability to carry-on the family’s active farming tradition while bringing in the skills and drive of a younger generation dedicated to the future of farming.

What has been the biggest surprise about the first year of the contract?

How much overall performance can be improved by making small changes and trying new things without changing the overall system.

What has been the biggest challenges?

Determining the correct investments in farm infrastructure that can bring down operating costs/improve productivity and recognising that sometimes these may lie outside the contract account.

If you were given the chance again, what would you have done differently?

Make sure the management accounts for the contract align as closely as possible with the production cycle. We now weigh calves to be over-wintered on housing and treat these as a distinct stirk enterprise in the subsequent year.

What advice would you give to other farmers looking at a contract farming?

Make sure you have a book-keeping system that allows for easy data retrieval and reporting. Try to find a contracting partner who will listen as well as propose and be prepared to listen yourself.

Be ready to communicate more than you may have found necessary in a tried and tested arrangement in the past. Farming is being asked a whole new set of questions and we’ve got to be willing and able to change. When considering options, four eyes are probably better than two.

What does your family think about the new farming venture?

They are delighted that, despite the uncertain outlook for farming, we appear to have found a flexible but reliable arrangement that has future-proofed our farming activity

Anything else?

Increasing attention on the environmental outputs from land could give rise to tensions between the farming business and the overall strategy of the holding. The key will be maintaining profitability in farming while enhancing the overall value of the estate – and communicating!

What Perry and Lorna said:

What attracted you to contract farming?

The chance to be our own boss and so we could make some of the hard work pay off for ourselves.

What was the biggest surprise in the first year?

The biggest surprise would be the amount of break downs and costs to keep machinery running.

What has been the biggest challenge?

Biggest challenge was getting the money for tractor and things you need – the banks wouldn’t give a shepherd any money.

If you were given the chance again, what would you have done differently?

Don’t know if I’d do anything differently – I’ll tell you next year!

What advice would you give to others looking at contract farming?

It’s definitely better than working for someone else, getting up in the morning and being your own boss. But if you’re not going to work day and night to make it work, don’t do it

What does your family think about it all?

Think they are happy for us. My dad was here for four weeks at lambing time to help and Lorna’s dad comes and helps when he can as he is a shepherd up the Sma’ Glen

What do your boys think about it?

The boys love it here, they like to get involved

Anything else?

It’s been the best move for us. We have to work hard but get up in morning and do what needs done your own way, but it’s hard to find self-employed help. There’s a need for more young people in the industry.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article