Cattle farmers are continuing to benefit from ongoing progress towards BVD eradication in Scotland, judging by the latest National BVD Survey conducted by Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health UK.

The fifth such survey attracted more than 1000 respondents from across the UK, with a quarter of these based in Scotland. Beef farmers again made up the bulk of the respondents at 61%, with dairy at 39%.

The survey revealed the estimated value of being BVD free was £44 per cow on average. This figure has been consistent over the last five years, showing farmers seem to have a strong understanding of the overall cost implications of BVD to their businesses.

“The consistency of the results over the last five years provides confidence that they are a true reflection of how this important disease is being tackled by farmers across the UK,” said Kath Aplin, veterinary adviser for Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health.

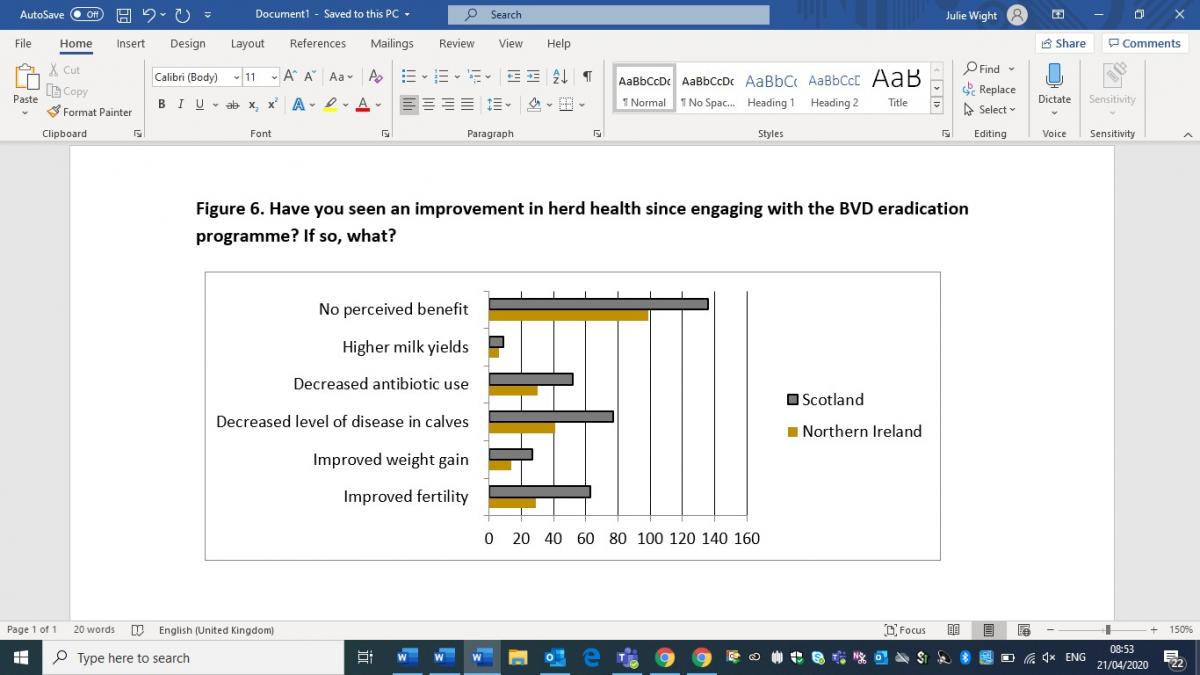

Looking at responses from Scottish farmers, 48% have seen an improvement in herd health since engaging with the BVD eradication scheme, even though 59% of producers in Scotland reported never having had a ‘not-negative’ BVD test result.

“It is reassuring that we can clearly see the health benefits of BVD eradication right across Scottish cattle herds. Some 20% of Scottish herds reported a reduction in antibiotic use since engaging in the eradication scheme. This is a good news story for Scottish produce – it shows how Scottish farmers are preventing disease and therefore, reducing the need to use antibiotics. The main health benefits seen are reduced disease in calves and improved fertility throughout.

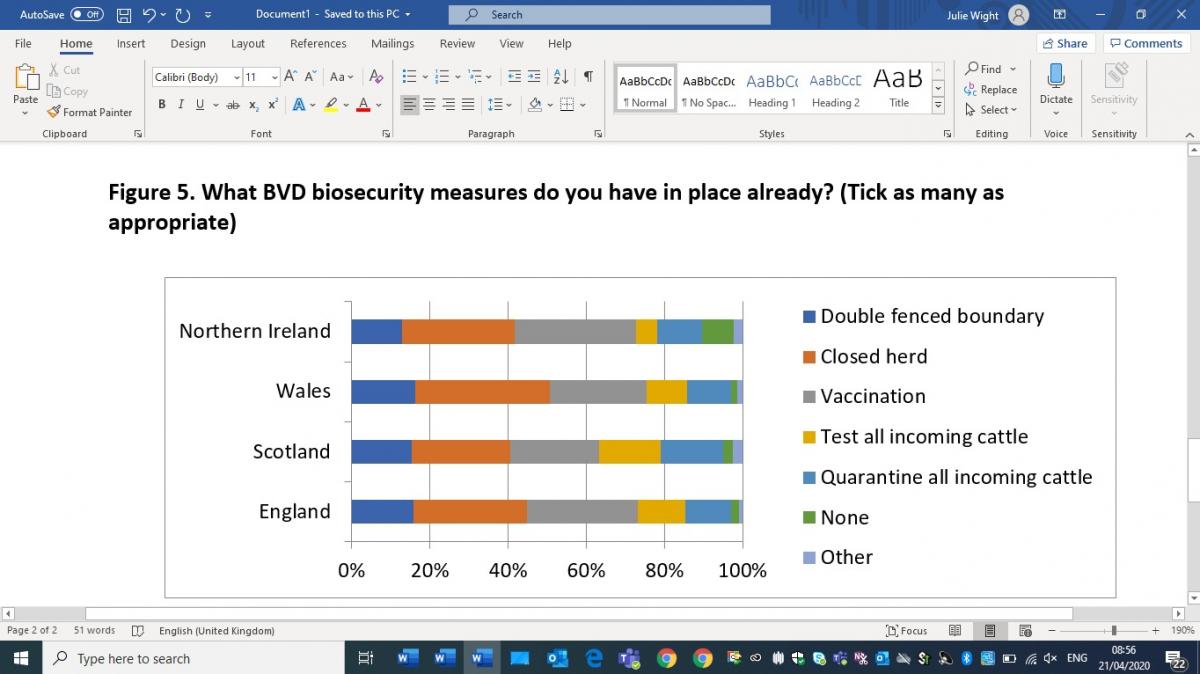

“As the BVD eradication programme in Scotland progresses it is encouraging to see most producers vaccinating, primarily because they value it as an insurance policy,” said Kath.

With ‘Phase 5’ brought in last year, the message is being ramped up that little bit more too, she said.

“Scotland is making excellent progress towards eradicating BVD, although it does still exist, so it is important that we stamp out the last bit of it, that negative herds are aware of any biosecurity gaps and maintain vaccination to protect their herd."

Iain McCormick, a specialised cattle vet at Galedin Vets in the Borders added: “A common complaint is that there are still probably too many cattle being sold through Scottish auction markets that are then deemed ’risky’. This shouldn't really happen – as only cattle from BVD negative farms should be sold on for breeding or further fattening – however it does still happen.

“The new owners now have to test them before they move again (within 40 days of arrival) but this is still a risk to the new farm as well as further unexpected expense. The compulsory BVD investigation (CBI) which is new for Phase 5, will hopefully mean that there are less of these risky animals sold as the non-engaging farms will now have to engage! However, if everyone engaged with the BVD scheme and its rules then there shouldn't really be any of these,” said Iain.

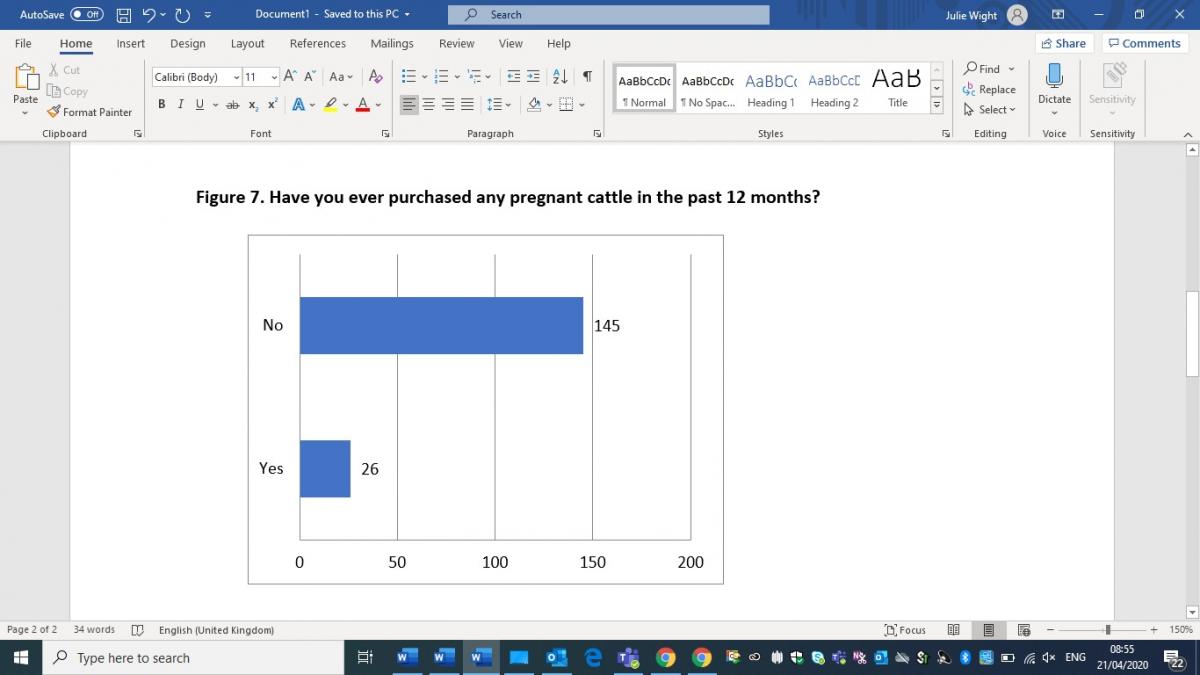

The major concern and the biggest risk to producers is bringing in stock to their herd. Furthermore, 39% of producers that purchased pregnant cattle admitted not isolating them or taking any precautions at calving.

“One of the big risks is buying in pregnant cattle – this should be avoided if possible, but if you really have to, then once the calf is born, it should be isolated until it has been tested negative for BVD as the cow can test negative but still be carrying a PI calf,” said Kath.

“From the May 18, 2020, new legislations will mean that any BVD virus positive animals will need to be isolated and housed separately on the farm. APHA vets will be randomly visiting farms to enforce this. We hope that this will also discourage farmers from keeping hold of PI animals,” said Iain.

The majority of respondents in Scotland use blood sampling to check for presence or absence of herd infection, with 84% (220) using it versus 44% (117) that used tag testing. For those who are blood testing, 61% test either five or 10 animals, with the remainder testing larger numbers of cattle.

“This shows that farmers are adapting the numbers tested according to the management groups they have on the farm, which is important when it comes to ensuring infection isn’t missed,” comments Kath.

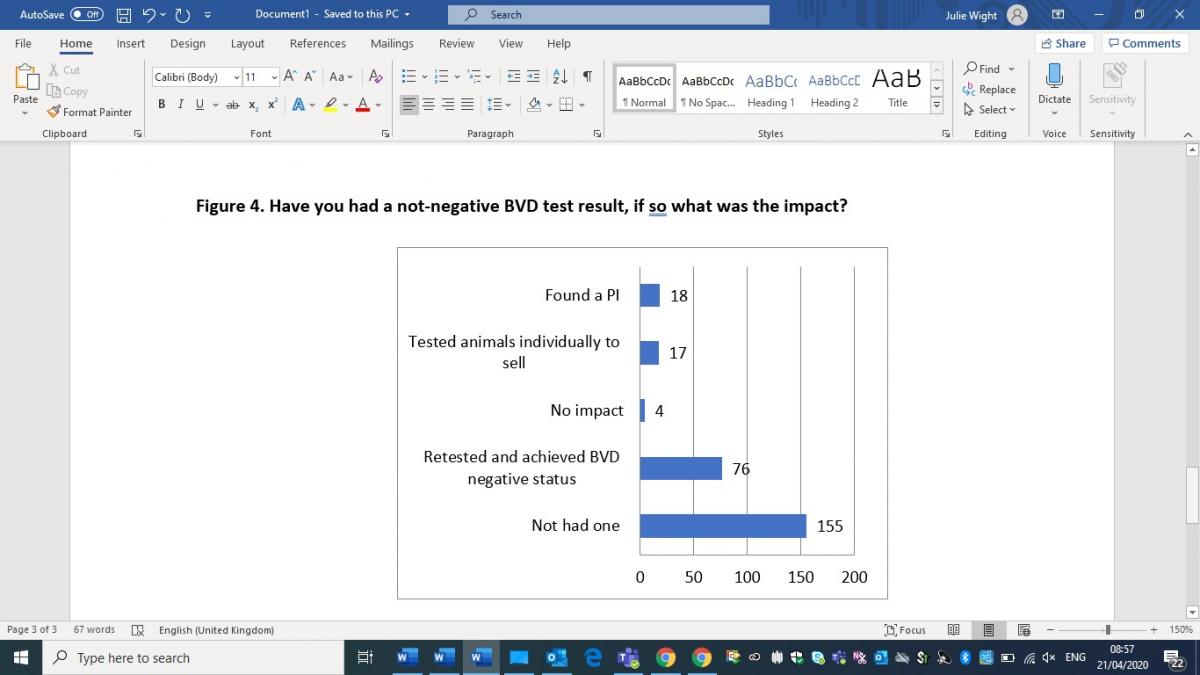

The frustration of getting a positive BVD test result can be significant, especially in Scotland where it impacts on a producers’ ability to sell on livestock. However, it is good to see that 66% of producers that had a not-negative BVD test result then went on to retest achieve BVD negative status. There were 16% however that did discover a persistently infected calf (PI). Encouragingly very few producers (10) try to hold on to or sell PI calves.

“Nevertheless, the key point here is that 16% of participants did discover a BVD virus positive animal after their check test failure, which highlights to me the importance of presenting the correct number of animals from each separately managed group of calves for the check test. If they don't present the correct number of animals from the correct management groups, then we could miss BVD on the farm. The take home message is do the BVD antibody check test properly and don't miss groups of calves that should be included in the check test,” said Iain.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article