Margaret Runcie, who has died aged 97, was a leading figure in the UK equestrian world.

Her Rosslyn Stud, which she founded in 1958, produced a stream of champion riding ponies over the next four decades both in-hand and under saddle. She won every major honour, landing a record 18 championships at her 'local' Royal Highland Show.

Outside the ring she was in constant demand as a judge, lecturer, administrator, advisor and breeder, helping to raise the standard and quality of native ponies across the country. Holder of two agricultural degrees from the UK and the US, she was honoured by her peers in both Scotland and England as a vigorous campaigner for improvements in breeding, welfare and show ring organisation.

Her attention to detail was outstanding, researching several generations of breeding to ensure the right bloodlines were used. She was proud that virtually every pony she led in a show ring had been bred by her, a feat practically unknown these days.

Born Margaret Mary Power in 1925, in Hatfield, Hertfordshire, she was the second of five children, growing up in comfortable middle-class surroundings – including a family trap pulled by ‘Buddy’ the donkey. Her diminutive stature led to her being nicknamed ‘Midge’ by her family.

An interest in ponies started aged three – riding the family donkey as a Shetland would have been too wide. At the insistence of her mother, who never had the chance to ride but enthused her daughter, she joined the local Enfield Chace Pony Club and went on to compete in showing, show jumping and cross-country events.

She also became friends at this time with local riding school instructor, Joan Middleton. Known to all as 'Miss Midd' she was to prove a huge influence on Margaret, with a strict but fair attitude to all forms of equine management and training.

Margaret was educated at Effingham House, Bexhill, Sussex, which was one of many girls schools of its type in pre-war Britain, with only 52 pupils. Wartime evacuation from the south coast meant the school ended up housed in mid-Wales, with Margaret leaving in 1941 having gained her School Certificate. She spent the next two years at home, and together with Miss Midd kept the Enfield Chace Hunt going, whipping in and exercising the hounds every morning.

By 1943, Margaret joined up and enrolled in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (the Wrens) and undertook nine months of training as a radio and radar mechanic. There she would often sit and watch planes flying at night along the River Thames past Battersea Power Station, the area being lit up by anti-aircraft searchlights.

In June, 1944, she was posted to the Fleet Air Arm base of HMS Jackdaw, based at Crail, Fife, and for the rest of the war served there as a radio mechanic. Her work was usually done at night and involved changing and recharging the batteries of planes returning from sorties across the North Sea, as well as repairing any of the valve radio that were not working.

She was assigned firstly to 786 Squadron which flew Barracuda torpedo bombers and later 785 Squadron which flew a similar bomber type named the Avenger. She was billeted in Crail House with other public school girls, rather than in the nearby barracks. By 19 she had risen to the rank of Petty Officer as well as grown in height, to the annoyance of the Commanding Officer who commented that her skirt was too short: “Wrens don’t grow!”

Demobbed in December, 1946, Margaret had applied for and passed the exams to become an aviation mechanic but was firmly told those jobs were reserved for men returning from the forces. She had already made up her mind for a career in the outdoors, having enjoyed life on the airfield, so went to Reading University to study Dairy Animal Science.

While there, she also coxed the women’s rowing eight and was in the first string at squash. Graduating in June, 1950, she joined the National Agricultural Advisory Service, in Leicestershire, as a milk tester, working mainly in Leicestershire’s Belvoir Valley.

In 1953, Margaret applied for and got a scholarship to study for a Masters in the US, at the prestigious University of Cornell, NY. She initially turned down the invitation to apply, reasoning: “I’ve got a super hunter who will win all the big shows this summer.” But was persuaded by her boss the offer was too good to pass up.

Along with other award recipients from England, studying a range of subjects, she boarded the famous Cunard liner, Queen Mary, to cross the Atlantic in steerage class. Their first task was to link up with a group of Scottish students who were also on board, and by placing themselves at all the exits from dinner they eventually spotted the ruddy-faced Scots agriculturalists.

The particular field of study with her Professor was modern milk transportation, collecting milk in chilled bulk tankers from farms and replacing small, old-fashioned churns left by the farm road end, and which tended to go off in the sun. This research paid off and within a decade 90% of farms in both countries were using this method to transport milk.

Having completed her Masters she was asked to travel to various types of farms to study modern farming techniques. Her companion was to be one of those Scottish ‘agrics,’ Ken Runcie.

They drove across America from the Canadian border to Salt Lake City, spending Christmas Day in the Florida Everglades. Returning to the UK on board the other great transatlantic liner, Queen Elizabeth, they were married in January, 1956.

Her new home was Langhill, a research farm on the outskirts of Roslin, south of Edinburgh, which Ken managed for Edinburgh University and which gave her valuable space to keep a horse. It was also the first farm in Scotland to use the bulk milk tanker transport system.

Although she continued to ride in the show ring, the imminent arrival of a son in the summer of 1958 prompted a switch to the smaller pony world. Margaret had always been particularly interested in equine breeding and Elizabeth Arden was a pony she was familiar with and had ridden in the south of England.

When the pony came up for sale, she immediately bought her over the phone, knowing it had all the qualities she wanted in a foundation brood mare for a pony stud – to be called the Rosslyn stud, the ancient name of the nearby village and the start of four successful decades of breeding and showing.

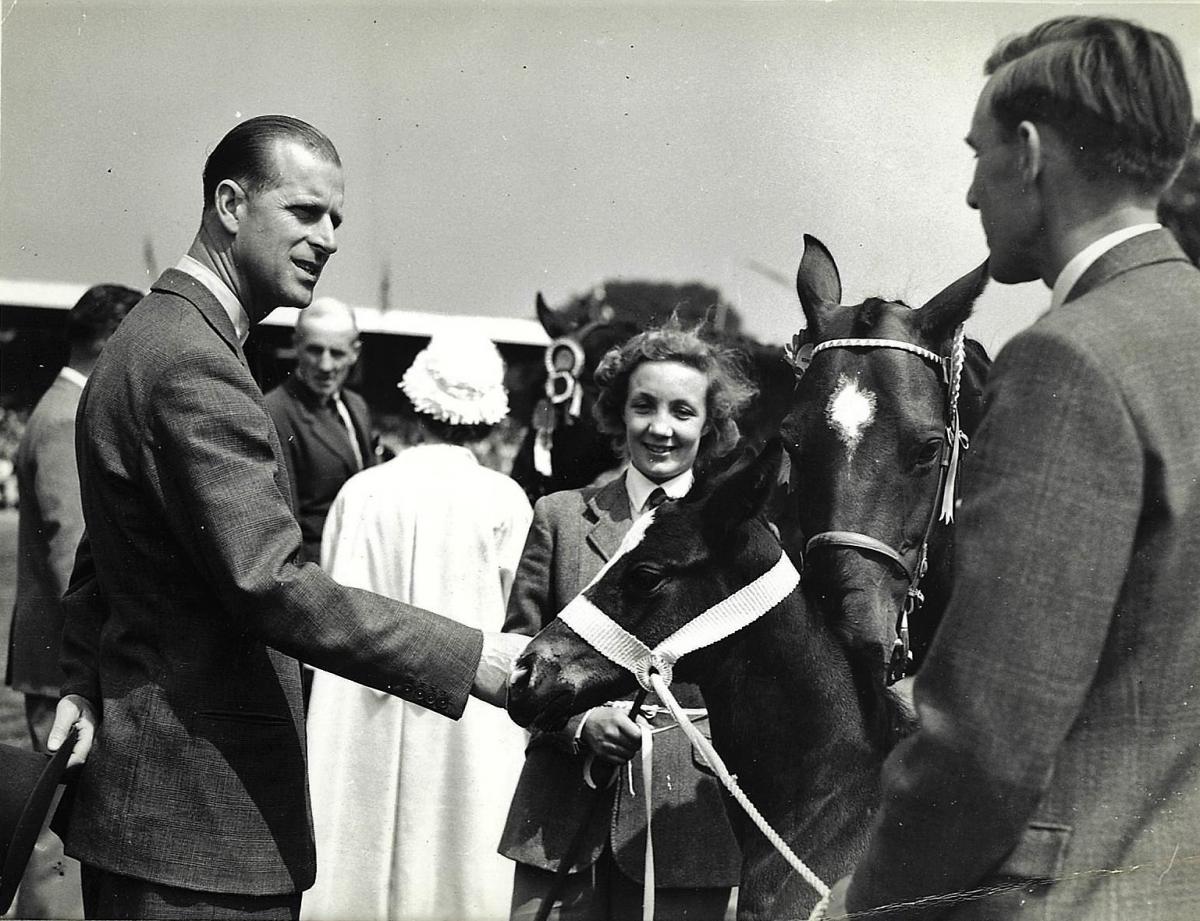

Elizabeth Arden’s career as a brood mare started successfully, winning the supreme championship at the 1960 Royal Highland Show, with the presentation being made by the visiting HM Queen and Duke of Edinburgh. It was the first of 18 gold medals won at the Highland by Elizabeth Arden and her offspring.

Success followed for the Rosslyn prefix and the need for larger premises was fulfilled with a move in the summer of 1967 to a small farm in the countryside to the east of Edinburgh, Garvald Grange, surrounded by 35 acres of grassland ideal for ponies.

Soon, the stud acquired stallions whose genes perfectly complemented Margaret’s mares as well as those of other pony owners who brought their mares to them. She also ventured south to the autumn foal auctions in Wales and was a familiar figure around the sale rings of Hay-on-Wye and other venues buying newly weaned foals. She particularly enjoyed jousting with the rugged Welsh-speaking hill farmers over a nice prospect, with the traditional phrase “Will you take profit?” usually sealing the deal. Many times she would arrive home in the small hours of the morning with a horsebox full of hairy Welsh foals, destined for life for the next couple of years as part of a herd in a nearby glen.

Her skills in the art of breeding were highly impressive. Sticking to one family and not following fashion, she had a clear picture of what she wanted. She was dedicated to breeding ponies of the highest quality, movement and temperament. They had to have clean lines, fine limbs and a good shoulder, and be well-behaved to suit a life around children.

Her success was down to her ability to analyse the strengths of her stock, breeding in improvements using specific stallions. Two of Elizabeth Arden’s particularly influential early progeny were Rosslyn Personality and Rosslyn Sweet Talk. Both mares had wonderful limbs, excellent temperaments and bred fine foals every spring until their late 20s. Nearly all youngstock were trained at home as 3 years old, as were the Welsh youngstock, all to be sold as children’s riding ponies.

Margaret had a tremendous work ethic. “We’d be at a show all day, get home knackered, yet she was off round the fields to check on the yearlings” remembers one of the many working students whom she taught for stud assistant exams. “She was always around the yard, and if we had to get up early to prepare for a show then she would get up too.”

Judging was a natural progression for her, though it was never planned. “Someone just said to me one day ‘do come and judge,’ and that was it. There were no judges panels in those days!” Her complete honesty and fairness together with an eye for good confirmation ensured she was always in demand as a judge around the country.

With her size, she also had the advantage of being able to actually ride many of the ponies in native breed classes. She was a popular figure at shows in Ireland, as one of the few judges happy to travel over from Britain in the 1970s when others were put off by ‘The Troubles’.

As well as success in the show ring she became influential outside it. Together with two friends, in 1961 they set up the Scottish Committee of the National Pony Society (NPS) in order to promote better standards and education among native pony owners in Scotland.

With Margaret as secretary the Committee worked tirelessly, persuading agricultural shows to put on more native breed classes and book better judges, setting up a transport pool to share long-distance costs from Scotland to the south, running an annual stallion parade to encourage pony owners to use better quality animals, putting on numerous demonstrations to educate people, even coordinating a Scotland-wide dried milk and colostrum scheme for orphan foals. She eventually served as NPS Scottish secretary for 33 years.

The telephone at home was never quiet, with people ringing up at all hours for help and advice from Margaret on any aspect of equine management, advice freely and generously given.

Already a Council member of the main body, Margaret became President of the NPS during its centenary year of 1993. At the annual show that year she escorted the Society’s patron HRH Princess Margaret around explaining what was happening.

She was asked to stay on for an unprecedented second year in office in 1994 and was also subsequently awarded their Medal of Honour. In 1995, she was the recipient of the prestigious Sir William Young Award from the Royal Highland Agricultural Society. Given annually to those who made the greatest contribution to livestock breeding in Scotland, the citation said: “Her success is in large part due to her attention to detail in all aspects of equine management. However those in the horse world agree that she has that intangible asset – flair – which separates her from her peers.” She was both the first equestrian personality and the first woman to be awarded this.

By the 1990s, the Rosslyn Stud had firmly established itself as one of the leading pony breeding studs in Britain, winning many championships across the country and more medals at the Royal Highland Show than any other stud. By this time the fourth generation of Elizabeth Arden’s offspring was picking up rosettes at major shows, in particular Rosslyn Sweet Repose.

This bay-coloured mare won consecutive “Highland” championships from 1994-7, including a coveted Queen’s Cup in 1996 and qualified for the Supreme In-Hand Championship at Wembley’s Horse of the Year Show five times winning it in 2001. Never beaten in a show class, many consider Sweet Repose the finest best pony Margaret ever bred.

By 1997, having wound down her stud numbers and moved to smaller premises nearby, Margaret decided to retire from running around show rings. The dispersal of the stud allowed her more time to judge, including trips to the USA, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, plus a continued involvement in many aspects of the equestrian world using her considerable knowledge.

She and Ken also enjoyed the world of cruising, and they completed 18 voyages before her 80th birthday. A final move to a sheltered cottage in Haddington followed in 2010, but she continued to keep up with people, events and shows until well into her 90s.

She was also an active and much-loved member of the Edinburgh branch of the Wrens Association, proud of her links with the wartime generation. Karen Elliot, Branch Chairman, said “We all loved to hear Margaret’s many tales about her life in the Wrens and beyond. She could be relied upon and was always a willing volunteer to represent our Branch and the Association at commemorative and remembrance services.

She enjoyed the opportunity to share some of her experiences with all she came in contact with.” Only recently in May, 2022, she was invited to be the guest of honour at a tree-planting ceremony to mark the late Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee at the Scottish Veterans Residences on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile.

Margaret’s husband Ken, recipient of an OBE in 1987, predeceased her in 2011. She is survived by sons Charles and Ian, and grandchildren Isobel, Charlotte and Grace.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here