NOTHING is more indicative of a situation coming to a head than the moment when talk turns from what could, should or might happen, to the single blunt question ‘who is paying for this?’

Like a restaurant dinner party in its final throes, when the guests no longer care whether they won or lost the conversational cut’n’thrust, all eyes at the great Brexit bunfight are now fixed on the bill.

NFU Scotland’s annual general meeting in Glasgow last week was a convivial and forward-looking affair, where a good fist was made of putting politics aside and all pulling together to make Scottish farming work, whatever its future financial circumstances.

However, in its closing moments, an unexpected game of join the dots produced the outline of a future that the industry’s leaders immediately recognised as total poison to their hard-won farming unity.

Mr Ewing was there repeating his pledge to maintain hill farming support by hook or by crook. Hanging in the air were comments from Central Association of Agricultural Valuers secretary Jeremy Moody that, if Westminster didn’t provide the extra funds needed to do this, Scotland’s Pillar One budget was the obvious place to find them.

All it then took was Mr Ewing’s lawyerly refusal to rule out any source of cash, however theoretical, for the departing delegates to get the distinct impression that the hills might be bolstered at the expense of other, seemingly more prosperous, Scottish farmers.

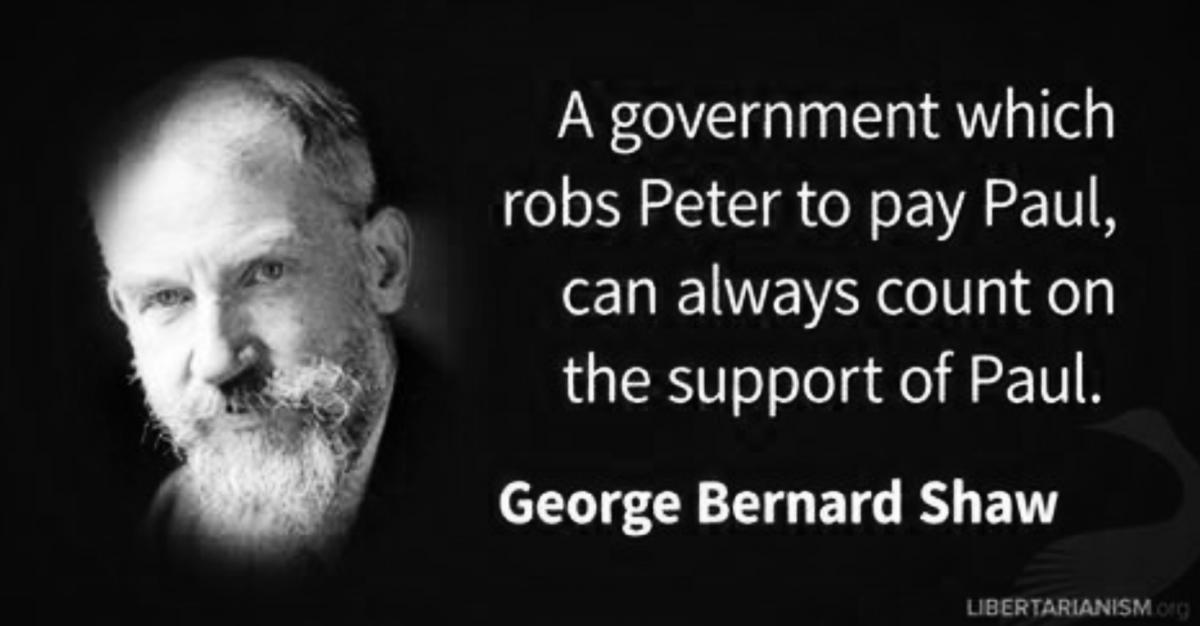

Both union and ScotGov spokesmen were quickly at pains to stress that this ‘robbing Peter (in his combine harvester) to pay Paul (chasing sheep across Argyll)’ scenario was no-one’s official plan, and would be avoided at all costs, in recognition of the basic interdependence of the Scottish livestock and cropping sectors.

But this tussle over LFASS is an early, and chilling, reminder that farming’s Brexit is essentially all about the future spending priorities for UK taxpayer money, once distributed by the EU, now to be decided by Westminster. If those priorities change, there will be winners and losers.

However, in very much the same vein, this week also saw the first public mention of the notion that purely political decisions that cost businesses real money may create a solid legal case for compensation to be paid.

As things stand, Theresa May’s brinkmanship over a possible ‘no deal’ threatens the entire UK sheep sector with serious market damage, and overnight losses that would run into the high millions. In a world where banks get bailed out and big international manufacturers get ‘compensatory packages’ to keep them on British soil, the sheep sector would have a better claim than most if a botched Brexit shuts off the continental sheepmeat trade.

Scottish farmers would just, of course, prefer to be paid for producing food for people who appreciate it.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here